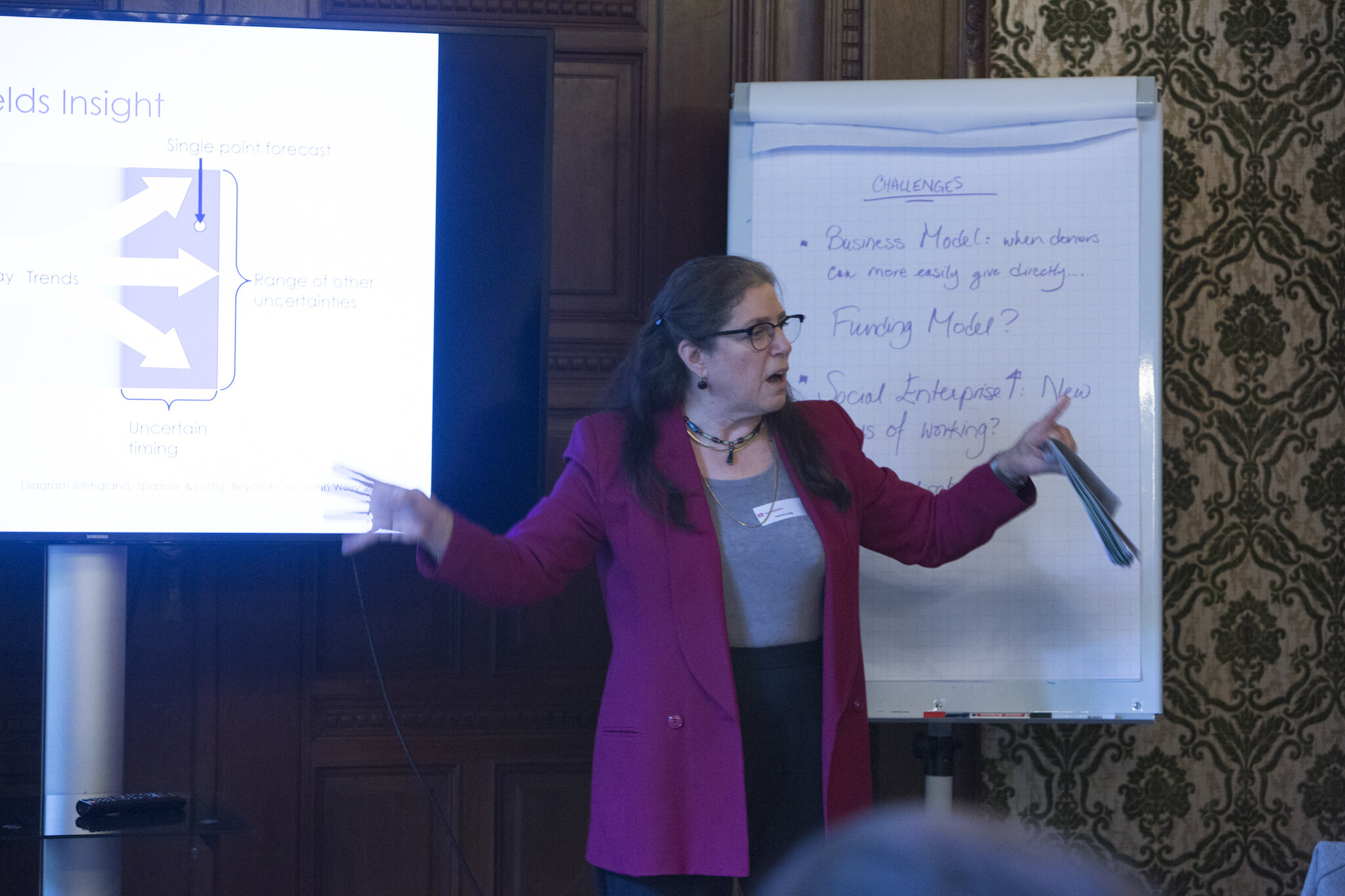

Patricia Lustig is an internationally recognised practitioner and writer in foresight, strategy development, future thinking and innovation. She uses foresight, horizon scanning and futures tools to help organisations develop insight into emerging trends and make better decisions for now and the future.

Originally from the Netherlands, Patricia is now based in England, in the United Kingdom.

Her intention is to help people to make better decisions for today, and, for the future for all stakeholders in the system – the planet and its flora and fauna, our children and their children.

Patricia is a self-taught, pragmatic futures practitioner who works in the people-space when the problem is not technical. She believes we should all use our foresight muscle and focus on making it stronger.

Patricia is a rule-ignorer who insists on Futures being of real use in helping make better decisions, often using an inclusive process of appreciative in-quiry to find out what resources are available, to uncover the necessary energy for change and, then, to find a way forward.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

Photography: Last three photos below taken by Rebke Klokke

More about Patricia

LinkedIn: Patricia Lustig

Twitter: Tricia Lustig, @Patricialustig and @LASA_Insight

Company: LASA Insights Ltd

References

Patricia’s Book : Strategic Foresight, Learning from the Future and Global Megatrends

Foresight In The Time Of Covid-19: Prediction And Uncertainty

Audio Transcript

Peter Hayward

Hello, and welcome to futurepod I'm Peter Hayward. Futurepod gathers voices from the International field of futures in foresight. Through a series of interviews, the founders of the field and the emerging leaders share their stories, tools and experiences. Please visit futurepod.org for further information about this podcast series. Today, our guest is Patricia Lustig. Patricia is an internationally recognized practitioner and writer in foresight, strategy development, future thinking and innovation. She uses foresight, horizon scanning and futures tools to help organizations develop insight into emerging trends and make better decisions for now and the future. Her intention is to help people make better decisions for today, and for the future of all stakeholders in the system, the planet, and its flora and fauna, our children and their children. Patricia wants to make a difference. Welcome to futurepod Patricia.

Patricia Lustig

Thank you.

Peter Hayward

So first question, Patricia, for the guests to tell their story. So what is the Patricia Lustig story of how you became a member of the futures and foresight community?

Patricia Lustig

Well, it's interesting because I studied stem, I have my first degree within quantitative methods. So that's applied math, and computing science. This is a very long time ago in the 70s. Then I went on to study mechanical engineering, I didn't get a degree, but I did a lot of the background work. And I worked in the field of IT for many years. And I got a bit bored with engineering problems, because generally speaking, there was a solution, it was less of a solution, generally speaking, we might not always see it, there was less of a solution when the problems involved people. So I'm doing an IT project. And the problem is not a technical problem. The problem is a problem between people. And that fascinated me. So I'm self taught on all of that. But I began to work in the field of helping people make change, of OD. And I had quite a long career in OD working for people like Motorola, and BP in OD. And I started to look at well, we've got change, how do we help people change? And I could not see a way to do that, without looking at the future. I don't believe in the stick side, I think you need to have a carrot. You can't really convince people to change. If they don't want to change, they won't, and you won't have organizational change. So the successful stuff, you've got to talk about potential futures. And I realized very quickly on that there wasn't one future and no one could predict, I knew that. And I started reading, I am self taught. And I read a lot. I read all sorts of things. I mean, from the OD side, I learned about systems thinking. And then I started looking at all sorts of different tools one could use for futures. In 1995. Motorola asked me to study scenario planning with GBN, which I did. And that just opened up this huge new playing ground for me about what else could I do, and I just kept doing that stuff, because I can't see anybody who will do change without a view of what will come out of it. And that's a view of the future. And I'm also extremely pragmatic. I'm originally Dutch, I'm still Dutch. And that means I was always asking those difficult questions. What's in it for me? What's it for? There is no point in doing something and spending time and money on it, if there isn't an outcome that's going to be beneficial for someone. And hopefully, for the people that you want to do the change. There's got to be something in it for them. So that kind of started me along that process. And when I left BP, BP went through one of their cycles. So OD was in and then OD was out, and I wasn't up for being an HR Manager. And I hadn't the training for it. They had strategy, I was doing strategy and OD. And they had that under HR, go figure. But I wasn't up for being an HR manager. So I started working for myself. And I've worked with lots of different colleagues. And I ended up doing futures and foresight, and coming up with really interesting ways, adapting tools. And it's just really exciting. Because people don't realize how much of an influence we actually have on the future. Most people, you know, that you can, not making a choice is also making a choice. Let's put it that way. And if we got more people considering different futures, and a plan A, B, C, and D, and we trained more people in this kind of thinking, you know, it's like a muscle, the foresight muscle, let's use the foresight muscle. I think we'd make better decisions.

Peter Hayward

Yeah, about when was this move from BP to being a solo practitioner.

Patricia Lustig

I'm not a solo practitioner, I have a company and there are other people in it. But I've been in the company on and off doing all sorts of things, usually around change, initially, since 1990, but BP I left BP in 2006. And from that point on, my practice, and the company was very much focused on foresight, strategic foresight; making better decisions, and making better decisions for the short and the long term.

Peter Hayward

And I suppose now you've got a chance to obviously, because I think, as we said, in our conversation, before we came on that organizational development has got its own rich suite of tools and practitioners. And then of course, you then moved into another sandbox with another set of practitioners and tools. Well, what were some of the connections you make between the two practice spaces?

Patricia Lustig

Well, it's to me, they're just they're part of the same. But it's very, very interesting that practitioners on one side tend to, you know, not even know about practitioners on the other. You know, it's really, really interesting. And so many of the futures pieces of work are: you come in, you do your scenarios with us - future scenarios - however you get to them. And we might or might not do something with that. But as futurists we're not normally employed for the implementation stage. And that's something I love doing as well. But there aren't, you don't get OD practitioners, generally speaking - and maybe I just don't know the right people - who do foresight. You don't get very many people who are in foresight, who do that implementation stuff. And then another thing is, you've got kind of specialists and you don't get very often people who have had, I don't know what the word is in English. So I've been an OD person in organizations, but I've also been on the business end. So I've also been producing products and running projects. And so I've had the experience of what it's like to be running a business, in the business, whatever that business is, as well as doing the kind of consultancy/ strategy/ implementation side of things. And there's not many of those.

Peter Hayward

Who are some of the people as you started to integrate, foresight in with your other skill set, or some of the people that, kind of, were important to you in how you developed your sort of hybrid practice?

Patricia Lustig

Well, you've got Wendy Schultz, who is the person who likes shiny new things, and introduces me to all sorts of shiny new things. And I love that, that is absolutely brilliant, because we together have developed ways to run some of these tools quicker because clients don't want to spend the money or the time doing things. So how could we do Pareto and get 80% out in a short amount of time. And I would have said, Richard Hames is somebody who I've known for a very long time, and asks me questions that really make me think. I think we do that for each other, frankly, but you know, he'll say something and I'll go, Wow, that, yes, I need to go and think about that. And that's really, really nice.

Peter Hayward

He stretches your brain, doesn't he, Richard.

Patricia Lustig

He does. And last, but definitely not least, is Gill Ringland, my co-author on three books and we're working on a fourth and my writing partner who wrote the - I think - seminal "Scenario Planning" back in the 90s. And we worked together at ICL. And, again, it's because of being a thinking partner and pushing my thinking, she loves to play devil's advocate, and being interested in everything, trying new things out. And it's great fun to write together when we truly do write together because we construct sentences together. It's - I've never worked with somebody like that when I've been writing together. But, you know, I have so many colleagues that I've had wonderful conversations with, you know, and a lot of them are in APF, fewer and WFSF, I mean, I'm not an academic futurist. I'm a practitioner, and a practical futurist. So I lack some of that academic stuff in the background. But it doesn't mean I don't write papers, it just means that I don't very often right peer reviewed ones.

Peter Hayward

It certainly hasn't stopped your writing. Let's go to the second question, then the one where I encourage the guests to get under the bonnet and talk about the methods and tools they use and explain how they use them and why they use and the way they do. So what do you want to talk to listeners about, Tricia?

Patricia Lustig

Well, there are actually two tools because I never pay attention to the rules anyway, I don't think. And one of them I know has been discussed before, which is Three Horizons. And we use an expanded version where if we're looking 30 years into the future, we look 60 years into the past, to help people learn how to recognize patterns and watershed moments. So that when you're going you start with that, so that when you go and look at the future, you might recognize something going forward. And just really quickly, one of the real strengths of that tool for us has been that people have difficulty sometimes understanding what strategy is, and this can be at quite high levels in organizations. And if you use Three horizons, people get it. It's just Oh, oh, is that what it is? I mean, I've had people say it. And for that, it's just a really wonderful tool, because you get so many a-ha's out of it. So I do love using it

Peter Hayward

is it's a very popular tool. Andrew Curry said, "Look into more than three lines on a paper", obviously. And that is a tool that you can use with almost any audience, depending on their level of sophistication, and how they think about time, change... The whole sort of notion of disruption, or, as I said, it's a it's a very, very flexible tool to work and talk with a client. I think it's a great tool to put in front of someone and talk across.

Patricia Lustig

Yes. And it works across cultures, which is really important, right? You know, I mean, you may need to be a little bit different in your explanation. But people get it relatively easily.

Peter Hayward

So you like to start with Three Horizons, it's that that's kind of where you start is that where you kind of start or start to get them into the conversation?

Patricia Lustig

That is one of the starting points in the whole futures process. But the one that I think people would be most interested in is an ending point. In as much as the futures process ends. It's an iterative process, an ending point, which is the tool of Appreciative Inquiry. It is American, it means inquiry with an "In" rather than an "En". Enquiry is what we would call it here in the UK, there is a difference. At any rate, the the tool itself helps you find out what your resources are. You've looked at the change that you need to make. So you would use Appreciative Inquiry when you had gone through your scenarios process, however you make your scenarios, and you'd stress tested your strategy or your policies or whatever that was. And now it's time to start the implementation process. So you want to know what resources you have, what resources you might need, and you want to - you need to - uncover the energy for change. Because if there's no energy for change, it will not happen. And Appreciative Inquiry is a tool that allows you to discover that, and starts to change happening almost by itself.

Peter Hayward

So talk more about how you uncover the organization's energy for change.

Patricia Lustig

So it starts with the finding the question you want to answer. And that is a really important piece of the puzzle. You have to ask the right question. Whatever it is, you know, I've used this in BP, I've used it in rural development in villages across Asia. And the question has to be key, and you need all the people who have skin in the game, or at least representatives from all the different stakeholders, who have skin in the game in the room with you, when you do them. You can do Appreciative Inquiries with a small group, or you can do it with 1000s. In Nepal, we did it with hundreds, a colleague of mine is done it on Aruba with 60,000 people out of a population of 100,000. You can self generate, you help it grow. It is an iterative process, like like the whole futures process is. So you define the question you want to ask. And in a village, just imagine - because this is simple, to give an example - just imagine you have a village of sort of probably illiterate peasant farmers. Question is, "What kind of a village do you want for your children and your grandchildren?" That's the real question. And the next thing is to go and discover what resources you have, what your strengths are. So you discover the best of what is and you ask questions around that and people interview each other. And then you can do a quick and dirty one, or you can do one that takes longer. And you can have kids going around and interviewing grandparents and people interviewing all the stakeholders and bring that in to the group and share and you know what you can build upon. That's what Discovery is about. The next piece is to do the visioning what they call Dream in AI-speak, but it's all jargon. It's visioning, you say these are the resources we have. These are the successes we have, what could we build upon it? Bearing in mind, we've got this question, "What kind of village do we want for our children and grandchildren?" What could we build upon it? And we discovered through the work that we did in Nepal, that getting people to draw pictures and not write, opens up a different side of their brain. And it was very interesting to do this in, you know, a mature economy and with people who are educated who don't want to draw, they want to write and we say no, no, you must draw, because that's visioning, it's about visioning. But I can't tough stick men and women is fine. Yeah. And it's wonderful. It's absolutely wonderful. What comes out, and you know, you do it in small groups together, and then you pull it together, and you have a big group. And together you assemble that vision of what could be. And then you look, you take it down. So it's converging and diverging, right? Yep. So the next step...

Peter Hayward

About Appreciative Inquiry, when I was doing it a long, long time ago, but what I brought into futures was I was taught that ability to check one's soft systems method, what he calls rich picturing? And using, you know, the cap while of you know, who are the clients? Who are the actors? Who are the owners? What's the transformation and that kind of stuff? And again the same thing was people, you you, you have to draw the rich picture. You can't give me dot points.

Patricia Lustig

Indeed. And you have to tell the story about it. It's also about narrative. Yes. And then you say, Okay, so here's where you're going to decide you're going to find the energy for change. You say, what hould we do? You know, what are the things out of this that we should do? And what's the order that we do them in? And what obstacles might we encounter? What problems or challenges are there? And how might we overcome them? And you start to get more into detail. So it's still, and I'm not sure should is the right word, but it's the kind of things that we ought to do, or we think are right. And the final piece is what we call Delivery. So it's what will we do? And that's a piece where people stand up and say, I will do this. And I will do by when, and I need help. If I've got help, I can do that. And what's the help I need? So this is kind of a bargaining place where we barter a way of who's going to do what and how and when. But it's only what people have the energy for. You can't make somebody do it. And so you will know at that point of time, what you can do. Now it's an iterative process, it means that the next time you meet - and you have to set up a time to meet - you go through the process again, this time, the Discovery at the beginning, is around "What have you done since we last met?" You can't stand up and say "I didn't do it". You can't, you're not allowed. You have to stand up and say, "This is what I've learned". And then you revisit the vision, is this still right? Do we need to add? Do we need to subtract? and then you visit the plan? Okay, what's our next steps? And then you go back to Delivery of the next pieces. And there's a monitoring piece in there as well, because you keep checking the vision against the question. You could even be asking, Is this still the right question? Does that make sense?

Peter Hayward

Yeah. And this is still action inquiry in the sense that people are longing to both do the work, but also inquire about the the work.

Patricia Lustig

Indeed, and if initially, it's facilitated, but after a few cycles, people can do it themselves. They understand the process, they've taken the process over. And this happens in villages with illiterate peasants, they will take it over and run with it, because it works. But part of that in going through the cycle, the second time is questioning, seeing what we've learned seeing what works seeing what doesn't. So it's a constant, sort of in OD speak plan-do cycle. We keep planning, doing, we keep, in a sense, prototyping, and maybe.

Peter Hayward

Yeah, that's right. And again, still inquiring still appreciating, to some extent possible building on. Yeah, so building on success. Let me say when you presented this to a group of foresight, people at one of the APF events that people were kind of blown away, and they've obviously you were saying that they probably hadn't heard of it or didn't know that it existed as a method for them.

Patricia Lustig

I'm not sure that's the case. I think many of them had heard of it, but they hadn't seen how it really worked. They experienced what it was like. And, you know, we in the hour that we had, we could only do interview each other on success, but it just, it galvanized people. It brings energy, it is a generative process.

Peter Hayward

Yes. If people wanted to know more about either Appreciative Inquiry or that kind of thing. I mean, are they resources that that are actually there for people if they do want to learn a bit more about?

Patricia Lustig

Well, they can read my book, "Strategic Foresight", because it's in there, but there is a resource called the Appreciative Inquiry Commons, AI Commons. And there's a lot of case studies, and there's a lot of materials there. I think it's affiliated with Case Western Reserve University because the person who developed Appreciative Inquiry was David Cooperrider, did his dissertation research on OD. And he's with Case Western Reserve.

Peter Hayward

Yeah, they'll be on your website with this podcast. We'll have some links to that for people if they're interested. Let's go to question three, Patricia, the one where I inquire I asked the guest to, if not put down their professional expertise, expert perspective, but just as a member of the human race, How does Patricia Lustig makes sense of the emerging futures around her? or whether it's your community or whichever frame you wish to place, but how do you make sense? What are you sensing of the emerging futures around you?

Patricia Lustig

Well, we certainly live in interesting times at the moment, don't we? And then watershed moments, pre COVID. And post COVID are very different things indeed. I mean, as a futurist, I do horizon scanning every day. And that's part of it. But I am incredibly curious. And I love learning. And so I'm always poking my nose into things to see what's going on and reading all sorts of stuff. I also read history because part of what is useful, is to understand when you see a pattern unfolding, being, you know, pattern recognition, looking at what's happening now, and trying to figure out which way a trend may go. So I just read an awful lot, and I talk to colleagues, and I've been very lucky to be on a couple of really interesting projects, I've usually got a few every year, they don't usually pay terribly well. But things like with the EC, looking at research and innovation and what that's going to be like in 2040. And these are things that make you think. So the discussions we have as a team, the writing up of the scenarios, the considering what it means. I think that's how I do it. And I think I would probably do a part of that, even if I didn't do this work, because I've always been interested in what's going on. I also write and when you write, you have to be very, very clear about what you want to say.

Peter Hayward

So you know, what things around you are getting your attention? Yeah, What things? Are you curious about, what you know, what sort of things are really got your interest at the moment?

Patricia Lustig

Well, I'm just watching what's happening around the world as the world tries to come to grips with COVID. It is fascinating, some of it's scary. We don't yet know what's going to happen. I think there's a lack of transparency, and people are afraid - people in power and government are afraid to say what's really going on and to say when they don't know. And I that I find fascinating to watch. And there's not enough really good, "Here's what's happening. Here's what we don't know, here's what we know", information out there, it's very hard to siphon off the good stuff. Does that make sense?

Peter Hayward

Yeah, we've been doing a series of special COVID short interviews with previous guests. And one of the things that one of our guests just said was, she has heard more of our language being used by leaders from time to time. In other words, people now are talking about having done scenarios, having looked at what the possible futures are having talked about uncertainties, she has certainly picked up that if not the whole the whole box and dice, but but at least this notion of the uncertainty and the emergence is starting to creep into some of the conversations.

Patricia Lustig

That's true. And I think that's also very interesting. And there's so much you know, what do you pick, but life is always uncertain. This is not any different. It's just far more in everyone's faces than it normally is. You know, these uncertainties, we face them about many things. I mean, we can look at climate change and say, how uncertain are we? There are some things we are very certain about, and others that we don't know anything about. It's the same with COVID. But COVID seems to be - because it can kill you - rather more in people's faces, it will kill you in the short term, as opposed to the slightly longer term, which is what climate change will do.

Peter Hayward

That's right. And there is the human figure of disease, which obviously, goes back any student of history would know that, you know, diseases and pandemics especially have been pivotal in human history and those things, things have changed dramatically through pandemics.

Patricia Lustig

Well, it's very, very interesting, because the book, the last book that was published was "Megatrends and How to Survive Them" that I wrote with Gil Ringland. And every single trend we looked at, we added pandemics to it. We said these are certain what is uncertain is the timing. I have never done a scenario set that didn't include pandemics. So why are people so surprised? And I'm not unique in this. I don't think any futurist worth their salt would not include pandemics. So it's just, you've got to laugh. You couldn't make it up?

Peter Hayward

Yes, I was talking to Sohail Inayatullah about a week ago and he was personally enjoying the fact that his world of being on airplanes and zipping around has stopped for him. And he actually is certainly looking at this pause - because it is a it is a long pause - that is actually seemed to have forced people to, if not take stock of where they are, but at least has given them a chance to pause and think about things.

Patricia Lustig

Well, I've got a mate who travels the world on FinTech. And he said, "You know what, I'm not going to do it anymore". He's got three Platinum cards with, you know, air miles, "I'm not going to do it anymore. I actually like being around my children and my wife". And, you know, I mean, for somebody like me, it's not that different. I didn't have a choice. I didn't travel that much. And I'm still doing the work. I like I just I'm doing an awful lot of it virtually. But I still get to do what I like. And I think I'm very lucky in that

Peter Hayward

Okay, so a curious person is thinking and paying attention to more than just COVID. So what other things are on horizon that are interesting?

Patricia Lustig

I mean, I'm watching the world move from what used to be - what I would call probably unipolar - to moving to a poly nodal world, as the center of gravity shifts back towards the east. You know, if you read history, it started there. And it's now on its way back. Very, very interesting, fascinating to watch. And, and, you know, it's difficult because we sit with our mind set, I cannot help that I was brought up here in Europe, I cannot help that I have that Western mindset, if you want to call it that, a mature economy mindset. And I tried very hard to get around it. But I can't, not totally. So understanding people with a different mindset is fascinating. And frustrating. And we need to do it. And challenging. You know, and I have Victor Motti, he's been he's been fabulous, because he pokes me in the right place to make me uncomfortable, and think about it.

Peter Hayward

If I just did an interview with Victor, and he told me all about the integral features of Persian philosophy.

Patricia Lustig

It's fascinating. It's absolutely fascinating. I reviewed his book. So I had to read it rather more tightly than I would have done if I just picked it up. And it's fascinating. And if it's at all possible to try to put someone else's glasses on, it's a fascinating, different playspace. You see.

Peter Hayward

Next question, Patricia the one, where I asked - this used to come up for me when I was teaching people futures and foresight. How do you explain what you do to people who don't necessarily understand what it is you do?

Patricia Lustig

This is one I struggle with a lot, as I think most of us do. I think that what I do, and what I would say to somebody who wanted to know, is I help people make sense of the world, to anticipate how things might develop and make better decisions now, and in the long term. I help them to understand what you can assume about the future and what you can't. So in a sense, if you are looking at uncertainty: what is truly uncertain, and what you can do something about, where you have influence. So at the end of the day, we have better decisions, both for whoever you are or your organization, but also for all your stakeholders, which includes the planet. That's the elevator speech.

Peter Hayward

If it's more than an elevator, and a person then leans forward and says, tell me more of how you do that. If a person shows interest, and a person shows, you know genuine inquiry, do you go deeper than that?

Patricia Lustig

Of course, because I love this stuff. It's I would say, it's about developing your foresight muscle. It's about thinking about what are potential different futures, good and bad? And how might we get there? If we can think of our vision, our perfect future, our preferred future? How would we get there from here? What are the different things that we might face challenges, obstacles, and how would we overcome them? That's about where it's jargon word sorry, where we have "agency" where is how do you identify where your energy for change is? How do you make change exciting, and that's about identifying the future that you want to work towards. And then people will ask questions about whatever it is that interests them, to go into more detail about it.

Peter Hayward

If someone responded the other way, to either cleanly suggest that it sounds like snake oi, if there is a kind of push back against the notion of people being able to create a preferred future. If you wanted to engage with such a person, apart from just walk away, what might you do in that situation?

Patricia Lustig

You have to understand I would want to understand why they said that. I mean, you've got people who are pushed so hard to be short term and they have no time for anything else. And then you know that there's not a lot you can do to help. You need to understand why they're saying that. That's a difficult one, Peter.

Peter Hayward

It's hard

Patricia Lustig

Most of the people I've encountered who have said, Well, I don't believe that, have been coming at it from, I don't have time to think that I need to do short term stuff, because that's what I'm being pushed to do. And I can't, I can't influence. And that's, there's not a lot you can do with somebody like that. Because I mean, I suppose you could suggest coaching and work with them on coaching to find, to create little windows where they could do something, even if it's only in personal space. But if there's no will, they're not going to do it. It's this whole thing about change. Look for the customer for change. If there is no customer for change, there is no change.

Peter Hayward

There is no change here. If this isn't helpful for a person who particular point in their life. Perhaps you walk away because to stay there is not going to help.

Patricia Lustig

Indeed, well, and I'll walk away from something where I think they're just going to put it on the shelf. There's no point in doing foresight unless you do something with it. Because it's a lot of work. Interesting, exciting, sure. But what's the point of doing it if you do nothing with it?

Peter Hayward

You don't always learns to work with people who are in leadership situations where they were trying to change other people. And always the question was, do the people actually you want to change actually want to change themselves?

Patricia Lustig

Indeed, the only organizational change that is successful and sustainable is change where everyone is involved in deciding what the change will be, and implementing it. So all the stakeholders are part of that discussion. And yes, it's a strategic discussion. But, you know, if you do that, and you do it, well, it kick starts and practically runs on its own.

Peter Hayward

The essence of Appreciative Inquiry to put the stakeholders in the room, isn't it?

Patricia Lustig

It is. And I've run meetings where I've had people saying, "Oh, I'm HR, why am I here?" Because you're a part of this company. That's, I'm sorry, that's I've had the same from finance. So you know, it's not just a particular group, it's not picking on HR. I don't do that.

Peter Hayward

Let's go to our last question, which is the open question, what do you want to talk to the listeners about for your last question?

Patricia Lustig

I'd like to encourage people to use their foresight muscles. And, you know, that means stretching your thinking, one of the great things about being a futurist is you get to read science fiction. Oh, wow.

Peter Hayward

Yes.

Patricia Lustig

I think that's fabulous. I love it. And you watch science fiction, and you pick the bits out. What are the bits you pick out? Well, maybe the bits that interest you, maybe bits that speak to you because of something you see today. There's work that Tom Lombardo is doing about the history of science fiction, and when science fiction is written, it's a product of its time. And that's fascinating to see. Absolutely fascinating. You know, what are people's visions and people, some people find it difficult. If people would like to learn more about strategic foresight, and particularly for non-practitioners, I wrote a book about it that won an APF award, "Strategic Foresight", and it talks about developing your 'foresight, muscles', and developing this way of thinking that stops closing things down and starts opening things up to possibility, to what's out there, because we cannot predict the future. That's the worrying thing. Peter, you are talking about more and more people saying scenarios and all these things. But in the same breath, they're talking about predicting what's going to happen or forecasting and that's, we can't do that. It harms our thinking to think that we can.

Peter Hayward

Riel Miller talks about for him of course, the phrase that he's going on with at the moment of course, is futures literacy, which at the core of that is our futures creativity, our ability to imagine wide ranging different futures.

Patricia Lustig

Well, and there's a piece that we call - and this may even be from some of Riel's work - we call anticipatory awareness. Awareness of how things might move. Awareness of what signals do I need to be looking for to say we're going one way or another, or a particular trend is moving one way or another. That tells you what you might need to do about it.

Peter Hayward

And of course, the study of the past doesn't predict the future. But sometimes the future rhymes with the past.

Patricia Lustig

Yes, I mean, I think the way I use it is what patterns do you see in the past? And are they repeating now? And what could that mean? Because just because the pattern is repeating now, doesn't mean we're going to get the same outcome. No. Well, what outcome might we get bearing in mind what we did last time? And it might be the same. I don't know. But it helps you ask yourself questions that again, open up to possibility, whatever it might be, possibility, whatever is going to happen is neither good nor bad. It's what we do with it.

Peter Hayward

Suddenly, the, the notion of the backcast, or the notion of looking back years earlier, does take away some of the hubris of people who say it's not going to be different. Because if you look back at previous times, you find in the past, people have had fundamental change dropped on their laps, and have had to change everything they do.

Patricia Lustig

We are human beings and human beings innovate and create, and give us a problem, and we'll go for it. That's what we are.

Peter Hayward

And try even a problem that we absolutely don't want to be in, we're actually in a problem, therefore, we've got to do something about it.

Patricia Lustig

Indeed.

Peter Hayward

Yes, we're gonna see a lot of interesting creativity on the back of COVID, as they try to open up economies as fast as they can, because people are terrified at the thought that the economies aren't going to open up.

Patricia Lustig

Well, I mean, one of the big things, again, that we look at is - what was very exciting for me - was that more and more people were coming out of poverty. And we were getting a middle class in places in Asia, and that was actually the motor of our growing economy. Now that's been set back decades, most likely, because they don't have a safety net. And so being three or four months without work will push them down a level and into possibly poverty. But if not, you know, very much at the bottom of - I use Hans Rosling's levels of level 123 and 4, and it will push them into level one or two, the lower levels. And then it takes a long time to crawl out of that. And that was the engine of growth for the world. So I think things will be different. I think it's going to be a very long time before we hit the same level that we had before COVID. If that at all. And we are going to have a lot more people in poverty than we had. And that's very sad.

Peter Hayward

Yes, we've also had some huge social experiments that we're running right in the middle. Things that people said we could never do we are now doing. The ideology got tossed out the window pretty quickly in a lot of countries, didn't it.

Patricia Lustig

It did. And that's also interesting. I'm really curious to see whether it holds. I'm curious to see what stays the same and what changes. I mean, the collapse of the oil price. Amazing. And what that's going to do to the energy transition, and many other things because we live in a great big system of systems. So everything has interconnections with other things.

Peter Hayward

I guess you would say that now is the perfect time to develop your foresight muscles, because you would not have more possible, exciting, weird things going on around you if you can take some time to become aware of them.

Patricia Lustig

I would indeed. It's very in your face. As they say, I think it's an American thing, isn't it?

Peter Hayward

It is. Well, thanks. Thanks, Patricia. It's been it's been lovely to have a chat. And thank you for taking some time out of your lovely days in the Lakes Districts and to spend some time with the Future Pod community.

Patricia Lustig

You're most welcome. It was a pleasure.

Peter Hayward

This has been another production from Future Pod. Future Pod is a not for profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support Future Pod, go to the Patreon link on our website. Thank you for listening. Remember to follow us on Instagram and Facebook. This is Peter Hayward saying goodbye for now.