Tamás was raised in a family of pedagogues. He grew up wanting to be a music conductor but ended up as Research Director at the Budapest Business School. He is interested in what wants to emerge in the world and what emerged for him after a decade of leading the Strategic Foresight program was a pivot to retraining as a primary school teacher.

He is increasingly focused on emerging generations and the futures literacy they develop. He observes the path dependency of emerging generations, they often carry images of the future that adults have given them. Instead he sees envisioning as an intergenerational process that the young teach us more than we teach them.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

More about Tamás

LinkedIn: Gáspár Tamás

Budapest Business School: https://uni-bge.hu/en/kkk

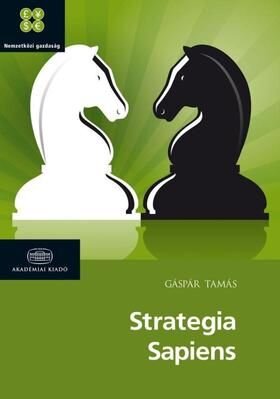

Tamás Gáspár: Strategia Sapiens. The sketch of a strategic foresight model. (In Hungarian) Akadémiai Kiadó (Publisher of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences), Budapest, 2012, p.354

CONTENTS

Introduction – Why Strategia Sapiens

I. THE CONCEPT AND THE MODEL OF STRATEGIC FORESIGHT

1. Sustainability and catching up – a strategic shift

2. Understanding strategic foresight

2.1. Foresight as a process of adaptation and shaping

2.2. The foresight paradox

2.3. Foresight as a responsible margin analysis

2.4. Foresight as a consistent system of aims and tools

2.5. Proactive adaptation – soundness and acceptance

2.6. Foresight as unfolding the intrinsic nature

2.7. Foresight as a public activity

2.8. The time dimension of foresight

3. The foresight paradox under unstable circumstances

4. An integral model of strategic foresight

4.1 Foresight - time-space structure and a systemic view

4.2 The conceptual frames and value guidelines of foresight activity

4.3 The historic-structural analysis of the on-going past visions

4.4 Status and margin analyses

4.5 Scope analysis – possible scenarios

4.6 Selection by targets – normative scenarios

4.7 Selection by mobilising forces – plausible scenarios

4.8 Efficiency analysis and systemic relations – desirable option(s)

4.9 The vision as a future portfolio. Operational foresight and strategic paths

4.10 Feed-back mechanisms – the elasticity and dynamics of strategic foresight

5. Summary

II. FORESIGHT AND DEVELOPMENT – A NURTURE PERSPECTIVE

1. The development debate

1.1. Approaches to defining the state of development

1.2. Development as freedom – ability and prospect

1.3. Caritas in veritate (Love in truth)

1.4. The foresight aspects of the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi report

2. The foundations of nurture – the first stage of development

2.1 The enculturation side

2.2 The individuation side

2.3 Intelligences – a systemic view of enculturation and individuation

3. System of components – the second stage of development

3.1 The individuation component system of a person

3.2 The enculturation component system

4. The system of competencies – the third stage of development

5. The complex level of consciousness – the fourth stage of development

5.1 A complex model of development

5.2 Development and measurement

5.2.1 Objective measures

5.2.2 Subjective measures

5.2.3 Crisis, sustainability and measurement

5.3 The systemic view of the complex development

5.3.1 The factors of consciousness level

5.3.2 Relation to the environment

5.3.3 The prism of the inhabitants’ evaluation

5.4 Different types of the state of development. Latent maturity as the start of development foresight

III. FORESIGHT AS ACTIVITY

1. Understanding the importance of activity

2. Foresight as future oriented activity

3. Interest (involvement) – the embedding category

4. The ranges of the future in terms of foresight activity

5. The academic and non-academic levels of futures thinking

5.1. Science in an academic perspective

5.1.1. The classical interpretation of scientific research

5.1.2. Paradigm shift in science concept

5.2. Non-academic field in an academic perspective

5.3. Differentiation in a non-academic perspective: the ‘saint’ and the ‘profane’

5.3.1. The time and future concept of the ‘saint’ and the ‘profane’

5.4. What can we learn from the differentiation?

5.5. Paradigm shift – the controversial emergence of scientific scepticism and the non-academic fields

6. Strategic foresight as a learning process

6.1. The system of learning

6.2. Interpretations of learning in a foresight perspective

6.3. Learning and growth in consciousness

6.4. Information and knowledge in a foresight perspective

7. Strategic foresight as experimental pedagogy

7.1. Sustainability and self-expression

7.2. The present versus the past and the future

7.3. Consciousness versus unconsciousness

7.4. Independency versus dependency

7.5. Nurture to complete

8. Activity and transition – the dynamic view of the system

IV. THE SPATIAL LAYERS OF FORESIGHT ACTIVITY

1. The spatial dimension of foresight and the strategic aspects of the social space

2. The layers of the foresight activity

2.1. Micro layer

2.2. Mezzo layer

2.3. Macro layer

2.4. International-regional layer

2.5. Global layer

3. The strategic foresight questions of the layers’ system

3.1. The spatial characteristics of the strategic foresight scope

3.2. The intensity of the layers in the strategic foresight scope

3.3. The space and time dynamics of the layers

3.4. The relations of the layers in terms of social atmosphere

3.5. A systemic view: fields of forces in the structure of the layers

V. DEVELOPMENT ERAS AND TRANSITIONS – A STRATEGIC FORESIGHT ASPECT. THE LOGISTIC–LIFE-CYCLE MODEL OF DEVELOPMENT

1. The logistic type of change

2. Life-cycle functions

3. The link between the logistic and the life cycle curves

4. The characteristics and the types of logistic development

5. Stages of development and strategic foresight tasks

6. The foresight aspects of transitions

6.1. Different interpretations of transition

6.2. The nature of transition

VI. SYNTHESIS AND PRESENT CHALLENGES – GLOBALITY AND GLOBALISATION

1. The world of globality – globality as completeness

2. The individual and her environment: mental, social and natural environments

3. The spatial and time dimensions of globality

3.1. Autarcheia and feeling at home

3.2 The self-space and self-time of globality

3.3 A systemic view: the complex space and time structure of globality

4. Uneven features of globality

4.1 Natural-individual constraints

4.2 Social constraints

4.3 The complex system of the natural and social constraints

5. Globalisation – a transition demanding strategic foresight

6. The controversies of globalisation

6.1 Controversies in self-strangling mechanisms

6.2 Controversies in self-correction mechanisms

7. Stages of globalisation and some strategic foresight lessons

7.1 The age of the world-models

7.2 The neoconservative turn

7.3 The age of chaos

7.4 The age of networks and terror

Transcript

Tamás Gáspár – Foresight as nurture

Peter Hayward: Hello and welcome to Futurepod. I'm Peter Hayward. Futurepod gathers voices from the international field of futures and foresight. Through series of interviews, the founders of the field in the emerging leaders share their stories, tools and experiences. Please visit future pod.org for further information about this podcast series. Today our guest is Tamas Gaspar. Tamas is research director at Budapest Business School, Department of International Economics, where he teaches in the Strategic Foresight Programme and also the PhD programme. Interestingly, Tamas also trained as a primary school teacher over a decade after completing his PhD, and he currently works as a primary school teacher as well. His research interests include socio economic strategic foresight and the intergenerational aspects of strategic foresight. He currently leads a research project strategic Foresight and childhood development. Welcome to Futurepod,Tamas.

Tamás Gáspár: Thank you, Peter. It's very good to be with you and with all the other people who are listening to this interview, discussion.

No.1.

P.H. Thanks. First question, Tamas is your story. So what is the Tamas Gaspar story? How did you become a member of the Futures and Foresight Community?

T.G. Honestly speaking, I've never been interested in futures … - in terms of what will happen. I was not enchanted by science fiction or so in the beginning, but there were some driving forces that created a kind of future orientation in me. One was of course the family. I was born in a family where almost everyone is a pedagogue back to several generations. So talking of development, nurture, constraint, how to help others step forward was an everyday topic at the dining table. Another factor was the spirit of the place: Hungary, which is a small country. It is located in Central Eastern Europe with a rocked history where creative thinking has ever been a means of sustenance, both in terms of adapting to or shaping the futures. Living here in Hungary is rather adventurous, but it is very similar to any small countries in Central Europe. Just look at the films or the literature of Czechia, Poland, Hungary, Croatia and others. The third factor is myself, because I have always wanted to be a musician, basically a conductor. But what I was interested in is not directing an orchestra, but rather the atmosphere and the structure of the music: how it is emerging. How the next tune you will hear is born from the previous. So a conductor in this sense. I always loved learning, for me which means being interested in the inner logic of operation; to understand the whole or the big picture. All in all the atmosphere of the future and not the future itself. Where all who is involved can feel well. This is my future and future orientation: to help it to emerge.

P.H. If so, if I can test what you're saying that I understand it is that it's really the process by which the future is brought into being through the interaction of people in society that actually is your predominant interest.

T.G. Yes, that's it. But I didn't realise that at all. You know I was graduated as an international economist and the big picture I wanted to see first appeared in space. I was very much interested in world economics to understand what's happening as a network in the world. This is why I was specialized in foreign economy strategy and I wrote my PhD in integration theory from a strategic point of view; which was basically foresight, not strategic in the strict sense. Later on I returned to the Corvinus University, where I also graduated, to the Department of Future Studies where I spent ten years. This was a completely new area; I did not know anything about futures of future studies. But it was very exciting to realise the whole, the completeness now not in space but in time; to realise that the further you see in the future, the further you can see in the past as well. So again it was not the future, I mean what will happen, which I was interested in but how changes take place basically. The other thing is that it was wonderful again realising the whole by occupation, meeting new subjects and new people in other research areas and understanding their logic. So working together with an architecture, a psychologist, a sociologist or an engineer and realising that their viewpoints or the way how their brains are wired are completely different than my one; and putting all these together to see that something completely new is emerging, – so this was wonderful. I loved it very, very much. This was the time when I was involved in the World Future Studies Federation as well with the support and encouragement of Tony Stephenson and all the other old fellows of the federation. We were organising the Budapest Futures Courses from 1999 to 2005, which was a fruitful experience and at the same time the World Conference of the word Future Studies Federation in Budapest, 2005, you may remember. I also became a member of the Executive board of the Federation and we organised another world conference in Sweden, Trollhatten. It was a wonderful period. This is how I was involved in futures studies.

After that you may also have noticed that I disappeared partly, I was withdrawing myself. On the one hand I went to paternity leave for almost two years with my smaller daughter, which was a splendid experience again: being together with a child who you are completely responsible for, including the creation of a fruitful environment, but you should let her develop, her own future emerge. Even if I was also very much involved in the first years with my first daughter, I did not realise that it's a completely different way of life and thinking, It was a real surprise that no matter how close I am, being involved in the nurture is completely different. I'm still sure that if all men in the world should spend half a year or a year at the paternity leave, the whole world would operate completely differently. The other experience, what you also mentioned was that I returned to school again and became a primary school teacher. Well, it was more than a decade after my PhD, which I feel a step forward anyway. Because here, very close to small children it was really possible to teach real literacy, of course including futures literacy and a kind of foresight thinking as well as socialising. But at the same time I went on with the university education. So it was really, really exciting that in the morning I was teaching the letter A or so and in the afternoon in a Masters or PhD course foreign economic strategy. What was indeed a surprise is that these two were and are not really far from each other. It is completely possible to share the same ideas with small children and university or PhD students. You can train the same skills, problem solving or socialising – also in terms of foresight and futures – of course with different tools, with different methods at different levels. The third experience was that with a colleague of mine who is also dealing with small children, we created a project which we call Singing and drawing, a kind of development or educational programme. However, we don't develop or educate, but we'd rather help children to do so. We open up the atmosphere in this programme for small children groups while singing with drawing, or doing physical exercises to music, all embedded in a fairy-tale. The feedbacks are very encouraging and we still do the programme since then. Later I had to return to the Budapest Business School, though I still have classes with the primary school pupils. I teach research methods to graduate students, macroeconomic analysis for masters’, which is rather the inside part of the foresight, and strategic foresight for the PhD students. I mentor three of them, too and hope they will contribute much to the futures work. Finally, just a month ago our university launched the Future Value Chain Centre of Excellency, which is a research centre where basically global value chains we analyse from different viewpoints from micro to macro- and international economics. What I'm interested in is mainly how the value chains are organised, how they change the production or consumption network and what future elements they have. This is where we are at the moment with the futures now, with my story.

P.H. So I'm interested when you said that you can be teaching letter A to primary school students and then teaching research methods to graduate students, but in many ways they are teaching or learning the same. Do you explain what you mean by that.

T.G. The similarity between the masters and primary school student is twofold. On the one hand, both the pupils and the master or PhD students still demand or need attention. Your attention. They are very grateful when you pay all your attention and your real time to them. It's not common sense. It doesn't go without saying that that everyone is paying his or her real attention to another person. And vice versa, when you teach foresight, strategic foresight or the elements of it, namely a kind of horizon scanning or finding driving forces; what kind of base line future you face; what kind of alternatives you see; how you choose from these alternatives; what kind of vision you have. All these elements are relevant with small children, because they face the same problems in their everyday life. Of course primarily not as, let's say, sustainable futures or environmental protection but in their very pure everyday life. If you have the opportunity to spend a lot of time, every day, every morning a week with these small children, step by step you can help them realise how to think in terms of different options; how to understand the different views of other children before they shout on each other. This was one reason why I returned to primary school because I realised that you have the chance to spend all your time with the same group of children for four years, every morning, and you can have a vision that is possible step by step to achieve. You have the possibility to monitor how children are proceeding, what difference they have in skills, in visions, in attitudes, in understanding, in behaviour and how to differentiate your own techniques and methods to help them emerge their own futures or their own paths of development. That is wonderful.

P.H. Thanks Tamás

No.2

P.H. Second question, we encourage the guest to talk to the listeners about a framework or an approach that is central to how they do their work. So what do you want to explain how you use to the listeners?

T.G.The experience what I have is foresight from a nurture perspective, which means two different things, one is foresight, strategic foresight in the university education and second, in the primary school education. In terms of university education I wrote a book almost ten years ago entitled Strategia Sapiens. This is about the background of a man who can think wider and further than usual. So strategy in this sense means rather foresight, and the book is the summary of my previous 15 year experience. The methodology or tool that I used as a foresight model is very close to integral futures, which was not that avowed at that time. Another key element of the book is that rather than emphasising driving forces or horizon scanning I put the attention to the insight aspect of the foresight activity, mainly to the real understanding who I am. This is where the whole process starts from, from an ontological perspective. Insight also involves the realisation how I think, understanding my own thinking and making it conscious, at the same time how the future I'm thinking of is emerging in my head. Finally, another feature is that the optional futures or the scenarios are linked very much to the acceptable and the achievable futures. The final assessment is a kind of cost-benefit analysis, an economist viewpoint to shrink the cone of the futures. And I think the last key element is considering the vision itself not as a single picture, but rather as a set of futures. The vision should contain a variety of the desired futures with very close links to each other to be able to shift among them owing to the changing environment. Writing this book was a challenge, because when I wrote it, I realised that my own understanding of foresight had changed a lot. So I was thinking if I had to rewrite the whole book. But finally I left it as it was, namely starting with one concept and finishing with a different one. In this case the reader can see that the writer himself faces a development while writing. Unfortunately the book is only in Hungarian.

P.H. You're saying that how you approached futures, and I agree it is very much like what I would say is integral features with which Slaughter was involved in teaching and I was involved in Richard’s programme: this notion that how a human develops their unique ontology, the unique sense of the world. And from their developed ontology they then effectively create plausible, possible futures, visions of possible futures. And they choose. You must have a theory of how people develop their unique ontology.

T.G. Well, this is the other part, dealing with children. This is why I pay more and more attention to children, to their education. In this case the methodology of futures practises is basically an opening up: to create a very open environment; to achieve an environment where children have no fear of the future, because they do have. I learned that it is very important not to have expectations towards children to make the maximum and to give the possibility to make mistakes (and of course also to correct them). Many times I tell stories of my own examples of failures and restarts. While no fear of the future is one pillar, opening up, thinking in terms of varieties of solutions is another. As I mentioned it doesn't go without saying, but it's possible with small children too, even in, let's say, teaching calculations. For example, 7 + 5 is a not so easy problem in the first year of school, and it has a widely accepted methodology how to get the result and how to teach it. But it was adventurous to spend hours with the children realising how their brains are wired and how they calculate and explain that to each other. The standard solution in education is completing first to 10, this is 3 from the 7, than adding the remaining 2. However some pupils said: no, no, no, it's much easier for me to know the double of a of a number, 5 + 5 or 9+9. So 7 + 5 is just two less than 7+7. Another one mentioned that: I imagine dominos with spots on it. So I see 5+2 as seven and 5+0 as five and I if I put the two dominos next to each other I clearly see that the five spots mean ten. I just need to see what is left up, 2. It is easy to say now: 7+5=12. – You can realise completely different ways of thinking, and if you let children use their own thinking or their own practise, also in terms of writing techniques sometimes, they'll find their own ways. Another pillar is that you should be systemic with these methods. This means that you should use them in the everyday practise. First, the exercises should come from the everyday practise of children. Second, using methods should be systemic because we should practise them until they become skills, competences. I don't really believe in weekend trainings.

P.H. One thing that has always fascinated me developmentally with futures thinking is you talk about. And you're talking about primary school children and their innate creativity and ability to see things in difference. But as I have experienced that Tamas, there's also an age, it's a little bit probably after primary school, when children start to almost socialise their imagination. They almost start to wish to ship to have common understandings rather than different understandings. So there seems to be both as you describe it, a period of time when children developmentally are happy to have unique ontology, and then I note that there appears to be another socialisation process when children start to. I say they actually are uncomfortable being very different and they want to be very similar. Does that actually get born in your observations?

T.G Completely. But what is more, small children don't simply want to socialise their notions to have a common understanding, which is regularly the case, but it is possible to teach them in the everyday practise to realise what other people or other children have in mind. If they have problems with each other, 9 from 10 times it turned out that the problem came from a misunderstanding: ‘what I see or what I think is completely different what he or she has in mind’. Throughout the years it was possible experiencing both, I mean sharing the differences and having common understandings. That is, okay, we have different views or solutions, but we can have a very similar result from the different approaches. They can accept that and what is even more is that children do not only want to socialise these visions, but they thrive on the teacher’s vision very much too. You know, the teacher is a God. They fully trust him or her. Everything what the teacher says is the truth for them. When I explain my dilemmas, my failures – that I do the same mistakes what they do; that I've never been an excellent student in my life – it doesn't mean that they lose trust in me as a teacher or in my vision. They trust it basically, but we can discuss it. We can criticise it. We can give options to it and it may be a mistake at the same time.

P.H. Do you find when you go from primary school into the university that in some ways you have to encourage graduate students to almost become as creative as they would have been as younger, younger children?

T.G. Yes, I think so in many cases. One reason may be is the education system itself, because after the primary years of creative work students tend to follow the curriculum or what the teacher says owing to the future stress. This derives from the entrance exam to a carrier supporting university, which appears in the secondary school, then trickles down to the upper part of the primary school as a fear not to get to a good secondary school. So the stress of the carrier perspectives strictly grabs even the primary school years both by the parents and by many teachers. By the years children get to a university, many of them have become trained to follow simply what the teachers say and they expect them to tell ‘the truth’ again. And it is a surprise for many children when they have the possibility again to cooperate with each other, to create their own visions or their own solutions. Of course this differs country by country, region by region. In some places it has a much, much better environment and tradition, in other places even worse. I experience that here in Central Europe many of the students love realising again that they have the possibility to think, to create their own solutions and to share it with the others.

P.H. That's good, that's good, thanks, Tamás.

No.3.

P.H. Third question one where I'm interested talking to Tamás Gáspár, Hungarian, human, about the emerging futures around you that you are paying careful attention to, either because you are excited by them or you are challenged by them. But of the things around you what are you paying particular attention to? And why?

T.G. Maybe it's not a surprise that among the emerging issues I pay special attention to the emerging generations. There are quite many reasons for that. One is that there are a lot of programmes and documents about vision 2050 from very different viewpoints. But these small children are the generation who will take the most of the burden of this vision. By 2050 they will be the economically active population, who should execute the future that we vision now and of course the questions arises: do they have to execute the vision of the past generation? From a futures point of view dealing with the emerging generations means the possibility to teach the future by concentrating on the futures literacy and foresight skills. But it's quite dialectic because on the one hand we have to share the visions of the present since in the short run it will be a path dependency for the growing up generation to live in. Hence they should understand how we considered the world and why. But these skills should enable them to be critical with these images and at the same time to be able to articulate their own visions in discourses. This is why I think that foresight itself or visioning is an intergenerational process in my mind. When we talk about foresight, I think we should take into account how the relationship and the discourse of the different generations are taking place, including teachers, parents and children. Many years ago, with Jose, Jose Ramos we wrote a paper in Futures concerning the generations and we tried to identify what generations mean and how they relate to each other in order to create different types of visions. Moreover, a further reason is for concentrating on the emerging generation as a future issue, because I feel that children teach us – at least as much or more than we teach them. So they expect us, teach us to become very clear and simple in articulating what we think. They teach us how to be honest, and how to be sober in mind, and committed or devoted in heart. Because when you are with children, every day is a new day. It doesn't count at all if you have a PhD, if you have a clear plan in mind what to teach, and also that goes for nothing even how successful or failing you were the day before – every day is an exam. You should clearly articulate who you are, what you think, and how you teach them. Every day is there is a new exam, but the good news is that there is always a chance to resit the exam. So this is what taking care of the future basically means for me.

No.4.

P.H. Fourth question, the communication question. How do you explain to people what you do if they don't necessarily understand what it is you do?

T.G. Well, regularly I do not explain what I do, I just do it. Mainly because I have very daunting experience in explaining futures work but I think many other working in this field have very similar experience. Either there is a non-understanding or a misunderstanding of the futures issue. Each person realising his or her own experience and understanding it is an easier way. Moreover, in most of the cases I'm not talking of what I do, but rather what I have done: the results of the research work or the teaching or the dilemmas I have found. It is much more understandable for people. Third, I prefer talking of what the participants of a research and students did to what I do. Because in this case other people can imagine much easier what a future work is all about. When I explain the process itself or what the reaction of the participants or the students was, or what dilemmas, what aha feeling they had. Again, creating the atmosphere, helping emerge it is much easier for me. This is very similar what I was talking about music, a conductor who helps emerge the atmosphere of the music. This is what I do.

No.5.

P.H. So the last question is your particular topic you want to talk to.

T.G. What came to my mind is the programme which all these different threads are flowing towards, namely the ‘Singing and Drawing’, because we're just preparing for a programme this week for a group of children. The birth and development of the programme were very exciting, in terms of foresight, because we had nothing in mind what this programme will look like. It was not a vision to develop a singing and drawing programme. This was just evolving. It's fascinating when you are one step behind something that is jelling in front of you and you have the chance to help it and serve it. This is not a loss of direction, neither falling a victim to changes. I don't know if you ever had this kind of experience when the vision is creating itself that is drawing you. Your task is to follow this vision, and all next steps appear in front of you, so you just do what you should do. This is what happened with this singing and drawing. When our children were small, it was wonderful to realise how easy it is drawing by a poem: you just follow the rhythm and the content of the poem. Then I asked what if we played music to it and sang, and it turned out that it was even much easier. Later on, as these children were growing up and started nursery schools, then primary schools, these institutions invited us. As we are teachers, we realised soon that the ‘podrongs’ (poem-drawing-songs) can be embedded in developing exercises as well as the regular developing methods and tools can be easily adapted. Hence we framed them into fairy-tales and completed to 45 or 60 minute programmes. Last autumn, in the covid period, once every week for six months we went out into a park and shared evening tale programmes for families. Each week a new one with new songs – well, that was the most fruitful period ever in the ten year history of the singing and drawing. It was also possible to follow it in the Facebook and one time we had visitors from nine countries, as far as Canada. I have never had a vision like this.

The background of the whole idea was that children have of course problems: obstacles, blocks that disable them to use their potentials. The aim of these programmes is to help children be creative, be independent in thinking and be active people who can shape their futures in the further life. This is why we link different developing activities at the same time. Another element of this programme is that in the ‘podrongs’ we start from one idea and transfer it to another. For example we can create a hedgehog from a fish or from a sleeping grandpa a bee is evolving; a mushroom gives life to a ladybird. This is a very good way of teaching children that the future is open to shape. If you start a mushroom-image, it does not necessarily need to be a mushroom in the future, but it may change to something completely different you want to shape it to. In addition, since the drawings that they (and we) think to be complicated are easy to follow, this is a very good tool to teach that complex systems have very simple rules and very simple building blocks, like in our drawings and our poems. Hence comes the third element of the ‘singing and drawing’ programme, that is the surprise itself. Wondering about something that is emerging, about the change itself has a very high energy. It is very similar to a research work. Any researcher any time can realise the feeling of revelation in the heart.

This programme is an experimental pedagogy. The future and a vision can be understood, or the understanding is vital only if you if you live it through, either directly or indirectly. This is why when we create a bear, a cat or a snow flower, the only way to understand how they function, how they think, if we ourselves become a bear, a cat or a snow flower. T

The last element I want to mention is the emotional or affective relations because I think that in order to be able to create our futures, the first fundamental is safety and the feeling of safety even if the changing world and uncertainty are common sense. Being conscious of the security of existence is very much necessary. This is just the opposite of the action of fear or the action by fear. If you feel safety by heart, you find the only way to create real or sober vision. This is why we call our programme ‘from soul to soul’. Our aim is to open up children in order to help them be able to create their futures and learn the tools and skills to do so, even if they will use them only in many years from now. But if all these are planted somewhere in their hearts and mind, when the time comes, they will know how to use them. That is for sure.

P.H. Lovely, that's a lovely one to finish on Tamás. Over half of the future pod community. Thank you Tamás for taking some time out to explain to us your fascinating journey from futures back to primary school and ultimately to create the next generation of future thinkers. Thanks very much.

This has been another production from future pod. Futurepod is not for profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support Futurepod, go to the Patreon link on our website. Thank you for listening. Remember to follow us on Instagram and Facebook. This is Peter Hayward saying goodbye for now.