Dr Karen Newkirk has lived and worked in Brazil, Peru and Indonesia (for 4 years) and on the Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in central Australia (for ten years). Global human development has driven her passion and led to a degree in Adult and Community Education, a Master in Business; Strategic Foresight and a recently completed PhD in Business, on the market for Indigenous Australian knowledge. Creating Eternity is the name of her business because she believes that life on this planet is capable of continuing for an eternity (in human terms). She sees the value of foresight embedded in First Nations knowledge, not only its’ applicability to the Australian environment but in mitigating anthropogenic climate damage globally and creating just human societies.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

More about Karen

References

Yothu Yindi Foundation, The Garma Festival: https://www.yyf.com.au/pages/?ParentPageID=2&PageID=102

Rosling, H. TED Talks:

(2006). Hans Rosling: The best statistics you’ve ever seen: TED Talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen#t-3261

(2009) Hans Rosling: New insights on poverty: TED Talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_new_insights_on_poverty?language=en

(2014) Hans Rosling: How not to be ignorant about the world: TED Talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_and_ola_rosling_how_not_to_be_ignorant_about_the_world?language=en

Rasmussen, M., Guo, X., Wang, Y., Lohmueller, K. E., Rasmussen, S., Albrechtsen, A., . . . Jombart, T. (2011). An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia. Science, 334(6052), 94-98. doi:10.1126/science.1211177

Nunn, P. D., & Reid, N. J. (2016). Aboriginal memories of inundation of the Australian coast dating from more than 7000 years ago. Australian Geographer, 47(1), 11-47. doi:10.1080/00049182.2015.1077539

Newkirk, K. (2020). Trading Places; Integrating Indigenous Australian knowledge into the modern economy. https://researchonline.federation.edu.au/vital/access/manager/Repository/vital:15124

Harari, Y. N. (2014). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind. Toronto, Canada: McClelland & Stewart.

Harari, Y. N. (2015). Homo Deus: A brief history of tomorrow. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Random House.

Image; Detail, Tiger Palpatja, Wanampi Tjukurpa, 2007. Acrylic on linen, 1015 x 760 mm. Charles Darwin University Collection. (714-07) on Tjala Arts (Ed.) (2015). Nganampa kampatjangka unngu; beneath the canvas: The lives and stories of the Tjala Artists. Adelaide, Australia: Wakefield Press.

Transcript

Peter Hayward

Hello and welcome to FuturePod I'm Peter Hayward. FuturePod gathers voices from the International field of futures and foresight. Through a series of interviews the founders of the field in the emerging leaders share their stories, tools and experiences. Please visit Futurepod.org for further information about this podcast series. Today, our guest is Dr. Karen Newkirk. Karen is a futurist facilitator and educator. Global human development has driven her passion and led to a degree in Adult and Community Education, a Master in Business; Strategic Foresight, and a recently completed PhD in business, on the market for Indigenous Australian knowledge. She is the principal of Creating Eternity, established in 2010. And she has facilitated workshops for Federal, state and local government as well as corporations and community organizations. She sees the value of foresight embedded in First Nations' knowledge not only in its applicability to the Australian environment, but in mitigating anthropogenic climate damage globally and creating just human societies. Welcome to Futurepod. Karen. Thank you, Peter. Great to have you. So question one, the story question what is what is the current Newkirk story? How did you become a member of the futures and foresight community?

Karen Newkirk

Well, at 15 I started with this passion for wanting humanity to be the best that it can be. I had some good teachers at Mount Gambier High School in South Australia. Ancient history was a bit of a disappointment because it only started about 300 bc and it was only about politics, but the teacher, Tim Jones, was concerned with modern in justices and would always refer to them and it was him who told us that the American military were putting warheads on dolphins and using them to put them on submarines and ships. I wrote to President Nixon in 1973, about stopping doing that, and and I didn't get a reply. I was concerned about the French nuclear tests that were taking place in the Pacific, and they were all over the news at the time, I was concerned about smoking, and had a pet peeve of my own about houses being built on the side of Mount Gambier all the way up to the lip. I thought it was so 'wrong', because it spoiled the natural beauty of the crater. And I thought that it was unfair that the view was only then available to people who could buy and build houses up all the way up to the top. So when the local YMCA decided, along with apparently all other YMCAs, that they needed to have a junior board. They contacted the local high schools and my name was put forward and I went along and the youth worker who was running it said he really didn't know what the junior board was supposed to do, 'so maybe we should just follow whatever you are interested in'. There were only about eight or six of us I think. We had three campaigns. The first one was stopping the French nuclear tests in the Pacific. I and others, took tape recorders and interviewed youth in our town and sent them to the French Embassy. We had an anti smoking campaign where we filled a huge jar with cigarette butts and asked people to guess how many were in there. And meanwhile, we handed out information about stopping smoking. One of the things that really struck me at the time was so many people said to me, "You will never stop people from smoking." And I was kind of floored, I wondered how these people thought anything ever changed. But you know, at the time we were surrounded with smoke. You couldn't walk down the street, you couldn't go to a restaurant, without cigarette smoke. We were surrounded in smoke in the 1970s. So, to some people, it was unimaginable that that could be changed.

Peter Hayward

Yeah. And normalized to the point where people are now offended if you smoke around them.

Karen Newkirk

Yes, that's huge turnaround. So, I have seen change. But the third campaign was about the houses being built on the side of Mount Gambier. We wanted the council to buy that six blocks of prime real estate land back and reserve it for a park. So, I wrote a letter to the newspaper, and we started a petition and wrote to This Day Tonight, and a film crew came down from Adelaide and interviewed us. And I think significantly, thinking about other forces at play and players in force. In 1974, which was the second year of what turned out to be a two and a half year campaign, it was the International Year of Youth, so the YMCA Junior Board was invited to speak to the Mt Gambier City Council. It took two and a half years, but eventually, that's exactly what happened. And those six, prime real estate blocks is now Seally Reserve and is still there, all these years on. That was my first taste of shaping human futures. I learned heaps. I also volunteered at the YMCA and I volunteered at the Department of Community Welfare as a Community Aid. I wasn't really sure what I wanted to do when I left school. But within five months of leaving school, I met an international human development organization called the Institute of Cultural Affairs. They spoke about 'bending history', which was their way of talking about shaping human futures. From the studies that they'd done on human society, they had a theory of social process called the Social Process Triangle, where they saw the three main elements as: economic, political, and cultural, where these elements of society were out of balance, and that the economic was dominating. They saw that the cultural realm was or should be the most influential. It's the one that drives human behavior. So, they worked on human story and human symbols as a way of changing human futures. They developed methodologies that are now called the Technology of Participation (ToP), which are facilitation techniques for involving groups in decisions. They did that, at the time through the 70s and 80s, through human development projects. They had demonstrations in each of 24 time zones around the world and then extended those and they had community meetings. Both of these worked specifically on desired futures. So, their strategic planning began with past, the present assets and future hopes and dreams; building a community vision. That was really where I learnt that 'vision' is very different to the sorts of strategic goals in something like a five year plan. The other thing that were part of these methods was identifying underlying challenges. I witnessed the success of these methods when I worked in a village in Peru. When the five year strategic plan was completed, they had infrastructure, potable water, roads, telephone, a clinic, health training, a preschool and early learning program, agricultural improvements, small businesses and community cohesion, which (they had heaps of community cohesion to begin with but) they enhanced by working together on their plan. And these were people who got up at five o'clock in the morning and worked in their fields or in their little shops all day, and then they would come with their lanterns to meetings every Tuesday night. There were 500 people in the village, but there were about 50 people who turned up to these meetings, with their little kerosene lanterns to discuss what had happened in the last week and what needed to happen in the next week in relation to their plan. In 2003, when I went back for the third time, they had several restaurants and a resort. [PH: Wow.] Yeah, wow indeed. This was completely laughable back in 1979. But the people there, who still had their original document (plan), were so proud to show me that part of their vision had been to have a restaurant. It had been an image of a preferred future that was unlikely and pretty unthinkable because people from Lima were very unlikely to drive down the Pan American highway for over an hour on a potholed dangerous road and instead of turning right to go to the beach, turn left and go for another 12 kilometers up a very dusty, dirty, potholed road to a community that had no electricity, no potable water and go there for a restaurant. But in 2003 they are very popular restaurants and the most popular had 600 diners for lunch, every Saturday and Sunday and now that's expanded, they've put on the third story. It is just an unbelievable story. But the underlying challenge in Peru is racial and gender discrimination. When I was there and saw the local Peruvian woman who was managing this restaurant, who was a lot shorter than me (and I'm only five foot two) so she was like 148 centimeters. When I saw her stand up to a 190 centimeter, light skinned man from Lima, and completely disarming him with her charming smile, I could see that deep change had really happened. And that was the point of the project to demonstrate that people could shape their own futures and not be looked down upon.

Peter Hayward

And you don't need elites doing it for them. Do you?

Karen Newkirk

No. Exactly, exactly. So jumping forward a bit. In 1984, I went to work and live on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands.

Peter Hayward

For the non-Australian listeners, you might want to explain where and what those lands are.

Karen Newkirk

Yeah, Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands are the top left hand, so, Northwest 10% of South Australia. That's just below Uluru. In 1981 they were granted the Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Land Rights Act. At that time, that land was supposedly under their control. During these years, for about eight years, the Australian Government had a self determination policy, short lived eight years. But the way that played out on the ground was, rather than "you determine your future", it was much more like "you tell us how you are going to become like us".

Peter Hayward

Assimilation was always the code wasn't it.

Karen Newkirk

Yeah, but it was still a different and hopeful era because there were quite a few people who believed in self determination and were trying to work for that. During that 10 years, I learned a lot. I learned that Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people knew a lot about how to manage the dominant society. They knew a lot about self determination. And it occurred to me that no matter how literate or numerate they became, the self determination that they wanted, was going to continue to elude them, as long as the non-Indigenous population of Australia continued to not trust them to determine their own futures. Bunuba, Human Rights Commissioner, June Oscar, worded this problem succinctly this year. So in 2021, this problem is pretty much the same. She said, we are not ever given the authority and capacity to make the decisions that affect our lives. Australian society is the pool from which all non-Indigenous staff go to work either on Aboriginal lands (as doctors, nurses, store managers, community managers, CDEP or employment program managers) or it's the pool from where the staff for all in the government departments stem. In the 1980s there were 80 departments, intervening or involving themselves in part of the lives of the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara communities. So, all of the staff that work for all of those come from this pool of Australian society. So, when I left in 1994, (on the one hand, it was still hopeful, because it was before 1996. And I guess that's a whole different history that we probably don't have time for. But it kind of marks a place where we started to go backwards), there was a little bit of hope. It was a time when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge was actually being taught in some schools. But I was wondering how this cycle of ongoing ignorance (on the part of Australian society in general) was really going to be changed. The only other thing that I learned while I was living there was that Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara peoples have a lot of knowledge that they've developed, and that has not been developed by Western knowledge. That was part of my question, how on earth could I as somebody who also barely knew anything about this knowledge could promote it as being important? It wasn't until the year I turned 50, 2007, that I encountered the foresight community, and that was in Ouyen. You may remember Peter, I met you, because you came to run a process with Steve Valance, who was one of your students. So, later that year, I signed up and started doing the Master's in Strategic Foresight, and traveling to Melbourne to do that course for a couple years. And it was there that I encountered the TED Talks by Hans Rosling, which was profound for me, because it gave me reason to believe that my optimism was well grounded, I guess, in my optimism in often talking to people about what's possible, people have often retorted that I'm just naive. But seeing Hans Rosling's statistics made me realize that, what I want and what I believe in, the possibility for not just humanity, but for all of life on Earth to be all that it can be, is feasible. We are in this huge universe, that we are the only life that we know of, and life is pretty wonderful. You know, we sense things we witness the wonder of the universe and we play our part. So I'm excited, I get as excited about longevity, as Allison Duettmann expressed in her podcast, but I'm not focused on individual longevity. I'm focused on the longevity of the collective of life on Earth; humanity and the biosphere. Excited that that could go on for as long as we can not even imagine.

Peter Hayward

Question two, which will be interesting is where I asked the guests to talk about a framework or a philosophy or an underpinning theory that goes to the core of who they are and what they do. So what do you want to talk to the listeners about?

Karen Newkirk

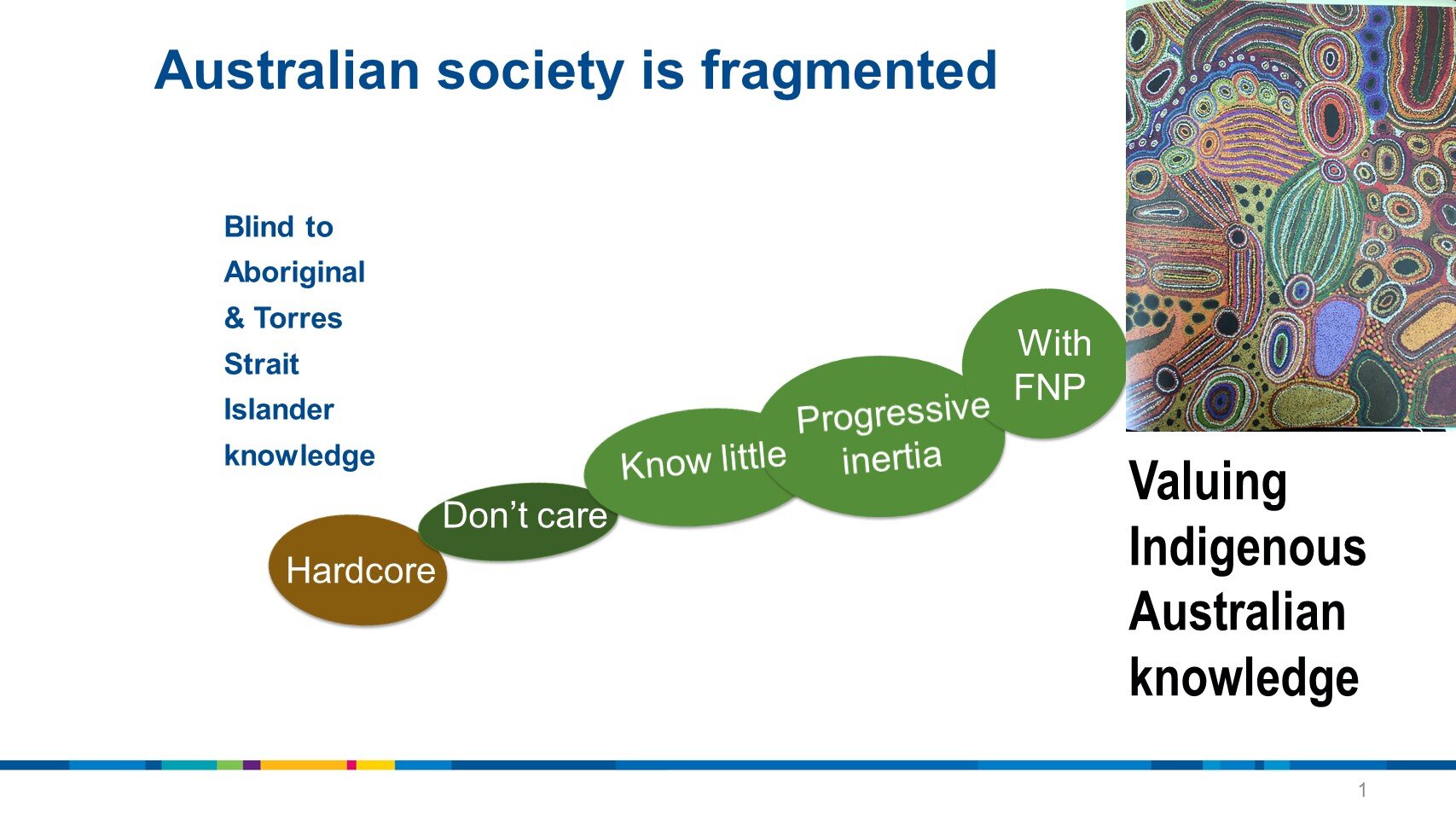

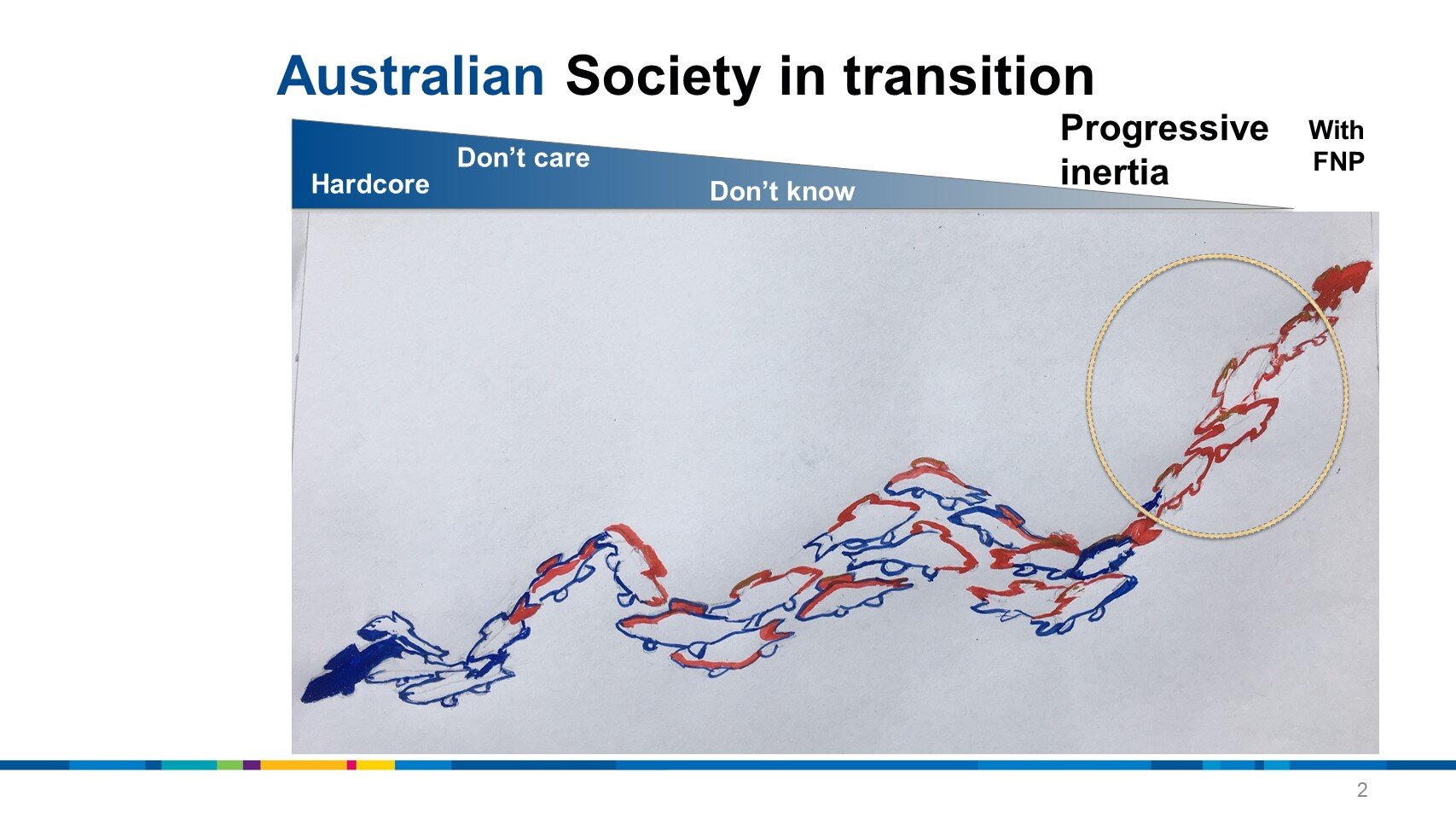

Yeah, so in the broad spectrum of possible futures, I've spent most of my career working on desired futures, working with people on visioning and strategic planning. I believe that our closest connection to futures is through our collective aspirations and our collective commitment, which generate our collective stories, which drive our purpose of humanity and possible futures. Yuval Noah Harari, who wrote Homo sapiens; A Brief History, makes the point very strongly that the power of human story drives human behavior. And a most important factor in determining collective aspirations is ensuring that all human voices are heard and the other voices of not only humans that haven't been born yet but the other life on this planet. All of that is important. There's a lot of futurists who work as facilitators, assisting other people to consider future possibilities. I spent most of my time doing that. One of my biggest gigs was with 89 people, considering the future of regulation for veterinary and agricultural chemicals. And there were 80% of the people in the room were men, and in an attempt to gain some gender balance, and also in an attempt to create a personal connection to the future of these regulations. I invited the 89 people there to bring along a 30 year old grandchild from the future, and also the opposite gender to themselves. It was a very simple technique to introduce as part of the strategic planning, but it turned out to be very powerful. And it did give people a personal connection. One of the other things that was said during the Masters of Strategic Foresight was that social change takes place through academic research. I immediately reacted to that and shot up my hand saying, 'wait a minute, what about all the social movements and I quoted Nicky Winmar pointing to his skin saying, 'I'm black, and I'm proud of it'. And surely Rosa Parks' actions and Martin Luther King's speech have been much more influential than academic research. But somehow over the following five years, I started to think that maybe I could do a PhD that might help non-Indigenous peoples to unblock their ears and eyes to knowledge and to the environment. One of the words that I heard so often on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands was 'watarku' (which I can't pronounce very well, because I can't pronounce my 'Rs' very well) but 'watarku' means 'oblivious'. People were always surprised at how oblivious non-Indigenous people were to the environment around them. An Aboriginal Education team from Western New South Wales, reported that "These ways of thinking and planning are our great gift to a world that desperately needs solutions... Unfortunately, this gift has not been accepted yet, or even noticed. This became the focus of my PhD. Why is it that this knowledge is not even noticed. In doing the PhD I was working on a desired future of my own. One whereby Indigenous Australian knowledge becomes part of Australia's knowledge and thinking, and something that's shared with the world as knowledge and ways of knowing that help humanity to understand that we are part of ecology, not above it. A few of the people that you've interviewed in podcasts have used those words, I framed the PhD using Wilber's, Integral Theory and All Quadrant, All Levels (AQAL) framework, because wicked problems (and addressing the status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia is a wicked problem) need to be addressed using a comprehensive, not a siloed approach. Big History is such an important part of Integral Theory and of Foresight, because models that are put forward as applying to all of humanity, that supposedly have been built on all of humanity, have not taken Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge into account. There are a few pieces of literature that I'd like to talk about that are significant to this statement. Futurists are just a microcosm of the larger society, particularly in relation to Indigenous Australian knowledge and a guy called Eric Moberg, who was reporting on the first international foresight conference back in 1969, stated that "there are primitive societies which could be called societies, for example, the Aborigines of Australia". This notion of "Aboriginal peoples being the most primitive people in the world" crops up all over the place in literature and media and even one of the podcasts somebody said, futurists sometimes say, "humans have evolved from hunting and gathering through agriculture". This is where I bring in some of this literature that Harari, who wrote the books on Homo sapiens, refutes that agriculture was a great leap forward for humanity. He says that Aboriginal people were exposed to the Western concepts of agriculture at least 5,000 years ago and rejected it, because they knew that they had a system that was superior. Agriculture, as it was practiced in Western and Eastern societies led to vast increases in populations, but also vast declines in the quality of human life, the quality of human knowledge and the quality of the biosphere. Only now are people starting to talk about projects being done on soil regeneration (to change agricultural practices). This is why Big History is so important to understand. If we don't understand humanity's real journey, we don't have any hope of understanding its possible futures. And another myth about Western knowledge that Harari debunks is that literacy was a great leap forward in human society. He says that writing lead to fraud. I was taught in school, as I think many Australians were, that verbal language is unreliable, it being like a game called 'Chinese whispers' (ironically). There's a PhD on sea level rise by Nunn and Reid. It's been done on 21 different Aboriginal language groups from around Australia as stories about sea level rise that have lasted for over 7,000 years that we know this because it matches the geological evidence in those places. Western knowledge has nothing comparable to maintaining such knowledge accurately for over millennia and over generations. When I attended the Garma Festival in East Arnhem Land in 2019, I joined many women before dawn. A day when the Yolungu women gathered us to sing. They sung for us about the dawn bird and as they sung, they paused and on cue, the dawn bird spoke. Also during that same Garma Festival, Galarrwuy Yunupingu told us that for every insect that you see, for every seed that appears on our country, we have a song for it. It's something that Harari says in his book, that hunters and gatherers had far superior knowledge about their environment, including astronomy, than others after the agricultural revolution. Another paper in my literature review is a genome study that was done by Rasmussen and a whole bunch of other people in 2011. In it, they conclude that there were two waves of modern humans who left Africa. The first modern humans left at least 75,000 years ago and these, they say, are the people who became the Aboriginal people who occupied Australia. According to the study, it was not until at least 24,000 years later, that the second wave of modern humans left Africa becoming every other human being on the planet. So, that includes the North American and South American Indian nations that were said to be about 15,000 years old. Not that that diminishes the knowledge that they developed, it doesn't. It just points out the uniqueness of the 60,000 year plus years of knowledge known to Indigenous Australians. First Nations peoples have attempted to teach this knowledge since settlers arrived in Australia but this aspiration has not been met with interest from Australians to learn. In using Theory U to explore the images being held by non-Indigenous peoples about the future of Indigenous Australian knowledge, I gained a lot of rich text. What emerged was a spectrum of attitudes, not only those of the participants, but of their perceptions of attitudes across Australian society. The barriers to perceiving Indigenous Australian knowledge are part and parcel of a meta-narrative that has been taught in Western knowledge. This meta-narrative and related metaphors negate and repel Indigenous Australian knowledge, equating it with early humans and discounting it as primitive and unchanging. Its innovations and adaptability have been concealed. Thus, propagating erroneous ideas about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that are prevalent in Australian society today, even among the more progressive thinkers. My thesis posits that there is a significant proportion of Australian society who hold on to attitudes of 'Progressive inertia', by which I mean 'progressive' enough to recognize that this knowledge is potentially valuable to human futures but inert because we still have these large splinters of the colonial narrative within our own thoughts. And we think that the problem is with the people who voice these ideas, and have even more racist ideas at the lowest end of the spectrum. However, by those of us with progressive ideas, removing these erroneous, preconceived ideas from our own thinking, we can progress Australian society toward the futures that we all desire.

Peter Hayward

Thanks, Karen. That's interesting. So interested move on to question three, because the one where I asked you to now just talk about the things you're paying attention to an emerging futures around you, you know, clearly, you know, with what you're thinking there must be things that you're seeing now that give you hope. And also, you're seeing things that possibly give you a concern. So, so what are the emerging futures that you're paying attention to?

Karen Newkirk

Existential hope in human society and in our biosphere. Going back to Hans Rosling's TED Talks, his main message is that the seemingly impossible is possible, and that we could have a good world. He says that the Gates Foundation and UNICEF and all the rest are saving the whole survival of the planet by making sure that the poorest 2 billion people have access to health and education and Rosling says that he's not a pessimist or an optimist, but a very serious 'possibl-ist'. [PH: Great term.] Yeah, and I think that that's where I sit. He says that the media has turned our fears into erroneous preconceived ideas. I guess that's what I see Australia battling with. What my PhD has been on is, what is it that non-Indigenous people need to unlearn to be able to hear the wisdom that's available to us, and there is so much Indigenous Australian knowledge that has survived, which is amazing. Rosling leaves us with four rules of thumb about the future, as a way to approach the future: that most things improve; that most people are in the middle; that countries need social development; and, fourthly, that the things that we fear are unlikely to kill us. The things that we aspire to can inspire us and lead us on. Don't be ruled by our fears; preconceived ideas about Indigenous Australian knowledge are more likely to lead to our downfall.

Peter Hayward

It is like your Peruvian restaurant. Yeah, here was a bunch of people that believed they could create a restaurant that people would want to travel to.

Karen Newkirk

Yep. It's our preconceived ideas about Indigenous Australian knowledge that's quite likely to keep us away from valuable knowledge that could assist us not only as a collective, but as individual people. If we knew more about our environment (through such knowledge) we could know more about how to mitigate and manage through climate change.

Peter Hayward

70,000 years experience of surviving on a fairly hostile planet, in a very inhospitable country, must teach a lot about how to actually sustain life.

Karen Newkirk

Yeah, exactly. Indications are that while the knowledge across the nation, with over 700 different language groups that developed different knowledge, the same kind of interaction took place in Australia that took place with the other wave of humanity, in that there was knowledge that was shared. People learned from each other. When I was doing the Masters of Strategic Foresight, I started thinking about four categories of knowledge that fit together in my mind as a kind of literacy of the land. And, I can't really talk about Indigenous knowledge, because I know so little about it, I have found that I need to give non-Indigenous people (especially those scratching their heads) some clues. One is the 21 stories from around Australia that fits into a category of 'enduring narrative'. Then 'acute observation', an example is of a Djadjawurrung woman who heard the larvae of a moth, under the bark of a tree, several feet away. And 'alert responsiveness', when Flinders sailed around Australia in 1801, he and his Marines docked near present day Albany, in Western Australia, and the Marines in his crew paraded on the beach, and the Noongar people were watching this and were able to re-enact that performance over 30 years later when the settlers arrived. What a superb example of foresight that the Noongar people showed in studying every move of these strange people who landed and kept performing it for 30 years (in case these people returned), from the person at the front, bending their elbow and putting their hand up by their eye and wiggling their fingers and the row of Marines copying it. That kind of detail, 'acute observation' and 'alert responsiveness' are part of what we need as well as 'enduring narrative' and 'holistic attentiveness'. Holistic attentiveness to our environment, we are starting to get clues of that from fire management. For over 30 years Western science has been studying First Nations' fire management in Australia, but so much has been missed. Because it's taken a long time for academics to actually start to pick up the level of complexity that's being observed and managed within what's going on (in the environment). One of my participants mentioned 'back burning' as a way of describing fire management, and it's so much more complex than that. Mazzocchi has a great piece of literature that I reviewed, that details the kind of complexity that we're really dealing with. I guess another great example is, the aquaculture that is at Budj Bim where the Gunditjmara people molded the hot lava, which poured 1000s of years ago, to create streams that enticed eels into their living areas, so that they had fresh food (without fences or refridgerators).

Peter Hayward

they were doing geo-engineering.

Karen Newkirk

Yes, exactly. So, it's not about dominating their environment but using the agency of the environment, working with the environment, to live with nature, and not dominated it, but to nurture all of our biosphere. This knowledge of reciprocity, rather than domination, it was true of genders and neighbors. Again, I'm not a person who can really speak about this knowledge, and there's so much more; human consciousness and spirituality that First Nations people talk about in books, academic papers, presentations, TED Talks, social media, tours, courses, programs and documentaries (Appendix 24 in my PhD, which you can download from the link below, provides some sources if you are unsure of where to start).

Peter Hayward

Thanks. Fourth question, the communication question. So how do you explain what you do to people who don't necessarily understand what it is you do?

Karen Newkirk

Yeah, I tell stories, like the ones that I've shared with you. You think that it's difficult talking about futures to people who've never considered it, try talking to Australians with preconceived ideas about Indigenous Australian knowledge, and add to that, that as a non-Indigenous person, I can't really speak about Indigenous Australian knowledge. I find that to be a real challenge. In both of those (situations) I tell stories. By talking with people, I try to find stories that create some traction, and also a bit of a stretch for them. There are some people who just won't hear [the truth in] some stories so I try different stories.

Peter Hayward

You are not talking, I mean, you don't mind talking to people down the end of opposition, but your real audience is the people that you think are closest to making the shift.

Karen Newkirk

Yeah. Certainly now it is. That's exactly the space that I'm in now; not worrying at all about that other end of the spectrum, but trying to get the Australian society to move forward by working on what I think is potentially the largest part of the Australian society, this category of attitudes of 'Progressive inertia', trying to have those people, ourselves, listen and learn and wake up to the idea that we can recognize our place as being part of the ecology, not above it, by learning this kind of knowledge. And not only that, but relationships.

Peter Hayward

I don't want to put it on the next generations to do this better. But is there anything in the generational shifts that you think gives you hope? That actually, is it possible that younger people are more readily to make the shift that you're talking about?

Karen Newkirk

Yes and No. Over the last 200 years there is moverment toward learning more from First Nations peoples. And certainly back in the 1990s, there was promise that younger people were learning things in school about First Nations knowledge and First Nations peoples were being invited into schools for a little while there until it was stopped. And there's no horrible story about what happened in education. Some of which are documented in the literature review, but the hope comes from people having access to knowledge and not being beaten down. If the people who are strongly committed to the colonial, racist narrative, if they continue to be in charge or in positions of influence with education, then no it's not going to help our younger generations. The reality is that as a nation, we are moving toward learning from our First Nations peoples, and wanting to know more about our biosphere. There are lots of examples around the world of people working on regenerating soil, things that are mitigating the damage of agriculture. So, there are all kinds of things that are happening that are moving us forward, and they continue to have an impact on a younger generation. There's that hope but the slowing factor is if we continue to allow these preconceived ideas to keep influencing our younger people that would continue to slow this process.

Peter Hayward

Thanks, Karen. Last question. In terms of closing off what you've said, we've covered a lot of ground on on your research and the fundamental nature of the shift needing to happen amongst the positive thinking people going forward.

Karen Newkirk

What I want to talk about here is preposterous futures; the unthinkable, the unimagined, the unimaginable futures. It seems to me that there are three human constructs that we can use to prepare for those. One is knowledge, some of which we've been talking about, and definitely, that which relates to knowledge of the environment. Secondly, something that you talked about, with Slaughter and Lombardo about Wendell Bell; enthusiasm for possible human futures. I think that that is crucial. A colleague once showed me a video of a list of not for profit organizations that were started after World War Two, they were inspired by wanting to work for human peace, and this list reached from the Earth to the Moon. The Hans Rosling statistics, and the way that he talks about the measures that show that human development is improving, is another. Also, whenever I've listened to speeches by Australians of the Year, they always talk about how profoundly humbling the experience has been because they started off the process, after nomination, with a room of 100 people who'd been nominated from each state and territory for all the various categories (the young and the senior and the local hero) and every one of these people has an inspiring story. That's 100 people every year. So just looking at the maths of it, 100 people who are actively working to shape human futures in a positive way. Australia's population is three thousandths of the global population or 0.03%. Therefore, there's at least 33,333 inspirational people over the world every year working on shaping positive futures, and that's more than I could ever read about! So, I think that there is plenty of reason to be excited about potential good futures. Thirdly, you also agreed in the conversation about Wendell Bell that, at the center of creating futures should be ethics, ethical values, and Zia Sardar also stated that all virtues are the only tools that we have to navigate post-normal times. Ethical values and virtues extend beyond our familiar images, so creating futures that are ethical and open require that we hone those virtues in the present. That we bring those virtues to bear on present issues, beginning with ourselves. To me, preparing for all possible futures means honing these qualities through dealing ethically with the real more moral issues of our time. Two of those are: how humans relate to our biosphere and how humans relate to each other. Australia has been given an important invitation in the form of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Our First Nations peoples have invited us to treat them as equals, something that this country is yet to do. I think that by taking up that opportunity, we are enabling a totally new, possible future for Australia.

Peter Hayward

That's good. So, Karen, on behalf of the Futurepod community, thanks for taking some time out to talk about your journey. Your very, very important work. And thanks very much for participating in Futurepod. KN: Thank you. Thank you so much, Peter. It's been fun. PH: This has been another production from Futurepod. Futurepod is a not for profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support Futurepod, go to the Patreon link on our website. Thank you for listening. Remember to follow us on Instagram and Facebook. This is Peter Hayward saying goodbye for now.