Robert is a former CEO with a deep appreciation of the challenges faced by senior leaders. His focus is challenging managers to think outside the known and consider alternative perspectives. For many years he was the Program Director for the ‘Futures Thinking and Strategy Development Program’ at Melbourne Business School.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward

More about Robert

LinkedIn: Robert Burke

References

Please see references within the transcript below.

Transcript

Peter Hayward: Hello and welcome to Futurepod. I'm Peter Hayward. Futurepod gathers voices from the international field of Futures and Foresight. Through a series of interviews, the founders of the field and the emerging leaders share their stories, tools, and experiences. Please visit futurepod.org for further information about this podcast series .Today our guest is Robert Burke.

Robert is a former CEO with a deep appreciation of the challenges faced by senior leaders. His focus is challenging managers to think outside the known and consider alternative perspectives. For many years, he was the Program Director for the Futures Thinking and Strategy Development program at Melbourne Business School. Robert has also written articles on the interrelationships between leadership, strategy, futures, complexity, and our inner realities. Welcome to futurepod Robert.

Robert Burke: Thank you, Peter.

Peter Hayward: Great to finally get this interview recorded. First question we ask all our guests Robert is the story question. So what is the Robert Burke story? How did Robert Burke become a member of the futures and foresight community?

Robert Burke: Okay. Thank you, Peter. Strangely enough, it happened after I became CEO. I realized that I had this position like many people in my position then your strategy as you, what you thought was your strategy, simply wasn't working. There was something missing. Although was a, CEO, I decided it was about time I actually learned something about being a CEO. That's when I did my Masters and my Doctorate, but it was based on really Action Learning or if you're like Action Learning in the Future, or Anticipatory Action Learning .

The main thrust of it was to use my own organization and myself as the case study rather than anyone else's. And this has been my theme through my teaching later on, is that although case studies are interesting they're of little value, if they don't actually relate to yourself, the best case study has to be your own self, your own organization. Where do you fit in?

I was very much influenced in the early days by people like Peter Eleyard, Malcolm Davies who ran Power Brewing at the time. And I guess it was when I heard these people speak, I became fascinated by what was possible from a futures point of view. I was then very fortunate to meet Sohail Inayatyullah. And we actually started the Future Thinking and Strategy Development programs some 20 odd years ago at Melbourne Business School, I understand it's one of the longest continuously run programs. Unfortunately, the pandemic has made it more difficult to keep alive but we do our best.

So what I've found though once I started to learn more about the future and more about future thinking, per se, is that it was really a story. That in reality, your organization didn't exist, all that existed was people. So if you wanted to change your organization, you really had to change the conversation.

And that, that became very important aspect of what I decided to do. So I started employing people who had really good knowledge to what we need in the business at that time, which was in the oil and coal mining industry, shudder to think of that, that now, but we would employee chemists, metallurgist, mechanical engineers, et cetera. But then my task was, to help them become better communicators, help them be able to actually serve our customers in a way that was more productive, more fun, if you like. So after say 10 years of trying this, the miracle happened and we became quite a successful organization.

At one stage, we were considered the most profitable organization of our type in the world on a per employee basis or productivity basis. So that was pretty gratifying. Earlier on the company that I had, Victory Lubricants, we soon merged with a UK company called Century Oils, a public company.

I maintained the Managing Directorship of the Australian version and a certain amount of shares. And that worked really well for about a good 10 years. Unfortunately, Century Oils was subjected to a hostile takeover and I was involved in that. We eventually lost, remarkably, I was able to keep my job primarily because we were quite successful. I remember the new chairman asking me, what do you do? And I said, really, what we're on about is service. We don't measure our success, about our bottom line, we measure our success about our customer's bottom line and difference to them. And anyway, I was able to survive that for a couple of years, inevitably the new owner, they have their their ways of doing things. I agreed to to leave and to pursue new things. At that stage I started my own organization called Futureware, and eventually, I found my way into the academia if you like into the Melbourne Business School.

Peter Hayward: Can I take you back to when you were the CEO of your company? And you said that it's about, if you want to change the organization, you've got to change the story they're telling themselves. Can you go more into what you mean by that? And also, if you were successful, what is it that people were able to do?

Robert Burke: Okay. I was very influenced by Ralph Stacey and his complexity work. And in fact, I had organized for Ralph to visit Australia for a week and to give his wisdom to us, if you like, at the business school. And I was influenced by his, the fact that when you said to me that I don't want to use any PowerPoint, I don't want to use any whiteboard. All I need is a circle. All I need is for people to talk. The power of talking. Some people couldn't handle that and left. That was okay. And I began to see that it really was our inner story, what we bring of ourselves to the work we were doing.. And when you said that if you think about your organization, whether it be Century Oils, whether it be Shell, that really doesn't exist, all that exists is you and the people, and if you want to change your organization, you change the conversation. And that rang a bell so deep with me that I began to have from then on two meetings. One I'd call a Leadership meeting when there was no agenda, and we just talked about what was emerging. I attended that meeting as the CEO.

The other meetings were your Management meetings, which I didn't attend. I thought it much better to people who were in charge of certain area, to get on with it. And then I began to see that my role was really one of constructive destruction. What do I need to do to destroy the company is existing in order to have a better company start to emerge? I think this is where I came face to face with some problems with my new owners. A German based company, also a public company who really couldn't understand that our success was due to the fact that we were relating at a far different level with our customers than was expected, but we were profitable. For instance, we had less than 1% of the global sales, but more than 10% of its profit. It was really working. And we formed really good relationships with our customers. I remember one coal mine, which is owned by a major oil company where the major or company insistent that they needed to do business with us, that my company was doing. So we agreed to do a six month trial. This was in the flotation area in the Bowen basin in Queensland is one of the major coal mines up there. So this company went ahead and did their six months trial. And we know they're the mining companies. Lost quite a few million dollars as a result. So we came in and did what we did, which was really add service to the product and developed a product that would handle all 14 seams, 13 seams of coal or whatever it was, and to really take on the role of being, looking after it for the customer. And the profit just went through the roof for them, for the customer. This meant that we could get off-tender, charging an appropriate amount of money, not a rip off amount of money, sometimes three or four times more than what was on tender, but we were far more profitable for them.

Peter Hayward: You said it, you were successful but, and I'm not saying this thing about Germans, but they couldn't understand. They were uncomfortable with what you would doing or they didn't understand what you were doing. Now I'm not asking for psychoanalysis, but what was going on for them? That what what you were doing seem so foreign?

Robert Burke: I wrote , quite a lot about this Peter. I call it the overriding influence of the Cultural Imperative, the Myth of the Bottom Line. So even though our bottom line was superb, we were doing things differently than the group were doing. And I think probably a lot of it was due to my own naivety at the time. I firmly believed that if I kept on producing the results we produced, then of course, I was safe, the company was safe as the way it was. That turned out not to be so .They really, even though we were profitable, they really didn't understand the basic methodology, the basic sort of inner a world that we were working in. The real commitment that we had and was pushing us to get into more traditional parts of the Oil industry. I saw no future in that. I couldn't see a little company like ours at that time, competing with Shell or competing with Castrol in the automotive world. I saw us existing only in the High Tech area. This is why I would employ really good technicians. Training them to be really good people, I don't mean that in any other way, but to be able to relate to the customer in a way that was deeper than just customer and supplier, a real partnership.

Peter Hayward: Was that difficult to do? We all know what the caricatures of engineers are, but was it difficult to develop technically oriented people into becoming very much other-centric in terms of the person they were working for?

Robert Burke: I started to sponsor a chair in Tribology, theory of rubbing lubrication, friction, and wear at Queensland University of Technology. And I managed to get Mount Isa Mines to be a 50% supporter of that Chair in Tribology. And to start to see people develop. And I guess I, I use that as my talent spotting.

Peter Hayward: Get them young before they get enculturated.

Robert Burke: I think so. And it also meant that I had to learn what they knew. I found that I had to go to Wollongong University to learn basic coal preparation and to the Julius Kruttschnitt Center at the Queensland University to learn advanced coal preparation. So I found that I had to learn the language as well.

Peter Hayward: I want to move you to Mount Eliza now because you've had this leadership experience in your own organization of both how you can create excellence in organization, but you've also had the, through the skin experience of how that can be received in hierarchical organizations. And then you stepped into the education space where I'd imagine you were starting to work with people who in theory wanted to become better at their jobs.

Robert Burke: Exactly. I was very fortunate at that time. I moved into the business school. I had been the CEO, et cetera, and had experience. I was very fortunate also to have a Deputy Dean Dr. Karen Morley, who was supportive of running a new program with Sohail. It took a lot of courage of her because of business school's "What the hell are we talking about here? We don't do futures thinking." Well, in that sense but we started the program started to attract very senior people, including CEOs.

And as I say, it had resonance over 20 odd years. Sohail was a particularly wonderful person to work with. I was continuously learning from him and we developed a process where, people could come to the program, we had a structure for them, even though it was about future thinking, it was still a structured approach that they could replicate when they got back to their own organization.

I think the defining part of the program was that we insisted that each participant apply what we've taught them to their own organization and make a presentation back. This gave them the opportunity to try the tools and methodologies in a safe environment and the hope that they would try them when I got back to work.

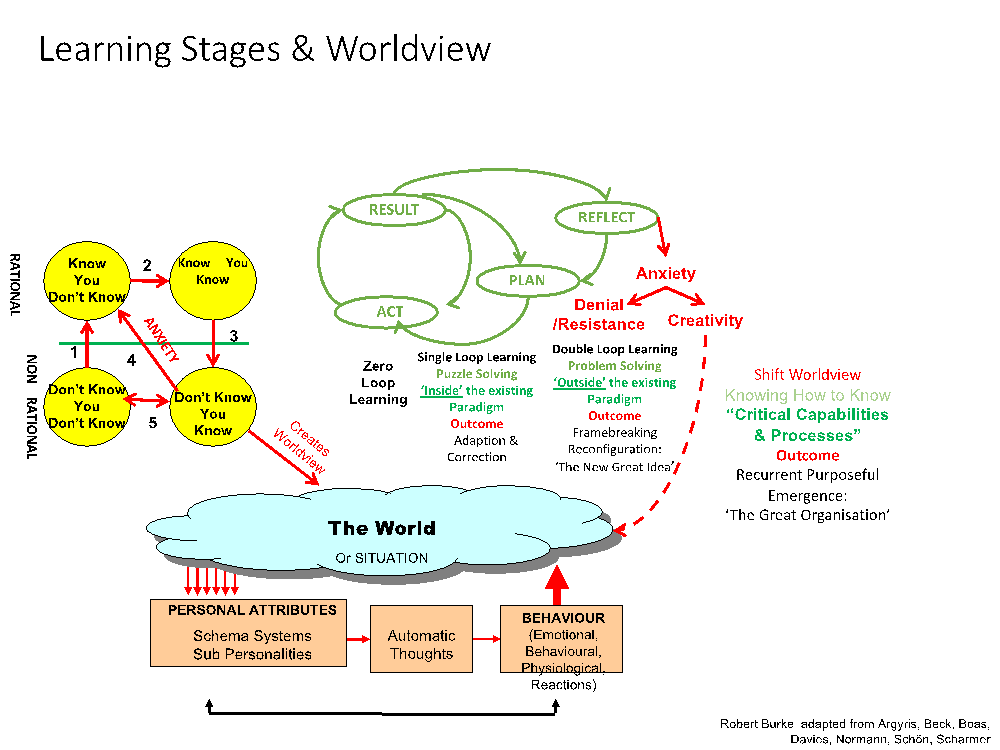

I would start the program talking about leadership and learning. Particularly the role of anxiety and learning. And here I was really relating to a lot of work of Heifetz and Linsky and Adaptive Leadership that less than 10% plans were considered ever implemented. And the reason for this seems to be that they were done at such a low level of anxiety and they usually have them with a vision being up front. And what we encouraged him to do is to use the futures tool and do your visioning last, because we wanted you to challenge your assumptions, where they might break down, what weren't you looking for? And then we would apply. Sohail's six, Pillars of Future Thinking, which the first four pillars, were the rigor of future thinking and the last two pillars, the creative alternatives and transformation was the rigor. Relevance and rigor.

Peter Hayward: You were starting with structure and you were starting where they were,

Robert Burke: Yes and we were trying to have a language that they could understand that didn't scare them, that excited them. We were trying to say that to be anxious was normal. And I recall the paper that Chris Argyris wrote in the early nineties called Teaching Smart People How to Learn. (need some help here Rob )Ron literally said the smarter you are, the more difficult it is to learn. And this had resonance with a lot of people that in order to learn new things, we had to let go of what we had already learnt.

So I was going through a lot of learning myself with people like Heifitz, Theory U with the scenario planning at Oxford and I got a visiting fellowship to Oxford. I did find that what we were doing, I thought it was going deeper, particularly with the work of Sohail. And 80% of the thinking was thinking upfront before you even did strategy. In order to get some sort of shared meaning that was both to use Sohail's terms, enabling that you could do it, but also ennobling that you wanted to do it in order to understand what your purpose was.

And to try to get them to realize what their real purpose was, you'd ask questions. "If your organization was closed down today, who would look better and why?" Yeah. "Which of your customers would miss you most and why?" And "How soon would it take for another customer to fill that void?" And these were questions that were Elizabeth Montgomery used to ask her Harvard class. I found it very useful in our work as well, that is where the idea of the creative destruction came in

Peter Hayward: They are deeply existential questions.

Robert Burke: Absolutely. But these, for people who were experienced Senior executives often CEOs, and we set it up at the beginning to say. It was purposely going to challenge your thinking, but also to give you reasons why you might think the way you think that you're how you protect yourself against anxiety was perfectly normal. And if we could look at ways of you navigating that anxiety in a productive way, you're bound to come up with a lot better thinking for you actually do your strategy. So the strategy part then became relatively easy. I did believe though Peter, that strategy is what you actually do in the present in the now. Strategic planning although useful was really just espoused. It wasn't strategy in action. So I was trying to get this over to participants that what you actually do in the here and now is your strategy. And so how you talked about it, how you created the story and how that story influenced what you talked about in the here and now became your real strategy. And that was the power of thinking.

Peter Hayward: I'm going to move us to the second question, because there's a number of things here that you've uncovered. This notion of anxiety and its effect on both leadership and the ability to learn. Again, it's a self-evident point, but most of the literature that talked about leadership was silent on the notion that leaders would ever suffer anxiety. We had the great man syndrome in all those things. Yet you found, or you had the, whether it was courage or just the naitivity to simply talk to people doing this work about, the anxiety they felt and how it impacted on how well they their job.

Robert Burke: Yes. I used to say to people that, to do leadership well was dangerous. You could get shot either metaphorically or for real. And the reason that is it required you to say things at times that people didn't want to hear and do things at time that people didn't want you to do, but it was how you went about that, how you went about navigating that anxiety that was causing you as a leader, as well as everyone else was the secret. And so Heifitz used to talk about this productive range of anxiety, where there was a sort of threshold of learning. Enough anxiety for you to start learning something significantly different, but there was also a limit to tolerance. It was only so much change you could take but the trick was to be able to navigate if you like between those parallel lines until you solve the problem.

And that was the adaptive issue. What had to change. Often people started off don't give up. And when you called that sort of letting go too soon you weren't actually leading anymore. So your ability to actually navigate that anxiety. Of your own and other people around you became critical, but it worked if you had the guts to continue it.

And this is why I think that too. Yeah. I became disillusioned a lot with our whole other leadership programs that were being offered. I found a lot of them were useful. I became accredited in most of them. And I began to see that people started to rely entirely on these programs. And a lot of leadership programs themselves were built around a particular model. And I didn't think that was the right way to go and try to limit the amount of what would you call it, influence from these models, but to increase the amount of awareness that the person had about themselves. How they confronted their own demons, how they were able to lead. But also how they were able to pick the eyes out of what the methods that were available could offer them, but to rely on them 100% and to build a leadership program, 100% of them to me was, kind've reactive.

Peter Hayward: The famous saying is all models are wrong. Some models are useful

Robert Burke: Exactly. So it's picking the eyes out of the good ones,

Peter Hayward: Something I want you to talk to listeners about, cause now we've had this conversation many times over lunch is this notion of people's inner life and developing your inner capacities in order to, both better manage anxiety or to some extent, move the lines further apart so you could stand more uncertainty, more ambiguity. Can you talk about, cause that to me is the magic, not that people can't manage what Heifetz talks about, but the ability that you can actually get much, much stronger at this by doing certain things.

Robert Burke: One of the first things I did when I joined the business school was to say what do I need to learn? So I enrolled in a postgraduate diploma in counseling and psychotherapy, mainly to deal with my own demons, but also to help me understand other people that understand how I could be a better teacher or facilitator.

So I found that by deep meditation, by really examining yourself and by having a philosophy of life that was based around doing no harm, to me was when I wanted to do. It wasn't about the bottom line so much though, that was important and we were good at that, but it was about how we could do no harm, how we could enhance. I think the people that we dealt with to, to have a better outcomes, but to do better things. So I started to encourage our people and I'm going back to the now, when I was a CEO, to learn. I allowed anyone in your organization could go and learn anything at our cost that they wanted to learn. Whether it be a university degree or knitting, I didn't care. All I wanted them was to have the opportunity to learn. And that became a strong motivator for myself. But in doing that, you started to discover things about yourself. Your inner world you weren't aware of before and some of this can be dysfunctional and in fact, drive you.

Peter Hayward: You wrote a paper on leadership and spirituality, you put those two words together and I could imagine you chose those words deliberately.

Robert Burke: I did. At that stage spirituality wasn't talked about much. Certainly in the business world. It meant a lot to me. And I think Sohail was very influential to me in that sense? As were you and as were Joe Voros and was Richard Slaughter. In Melbourne, there was a particularly strong futures world that I experienced to be cooperative rather than competitive which was wonderful atmosphere to work in. And knowing people of your ability who could fill in for us if necessary it was really important. So I cherish that.

Peter Hayward: It was classic altruism and self-interest Robert because you had a successful futures program at Melbourne Business School and we were trying to keep a futures program going at a small university. I used to use Melbourne Business School as a reason to say "They support futures. Why don't you support it?

Robert Burke: And we used to use our program to support the Swinburne program, you really want to learn more. Why don't you enroll in the future program?

Peter Hayward: Collaboration is an amazing way to build resilience in the face of uncertainty.

Robert Burke: Yes. I'm going to say at times Peter, I did resist joining certain groups, mainly because I felt that futures thinking should be wide open and I didn't want it closed in. I didn't want me to be closed in by certain rules and perspectives. I felt that the future thinking being so open was it's strength.

Peter Hayward: I want to move you to the third question, which is I'll get Robert Burke, futures program director and CEO to put all those titles down and just talk to Robert Burke, human being about the emerging futures that you see, that you sense, that you're aware of. What is getting your attention and why. . What are the things that excite you possibly? What are the things that possibly cause you concern, but the emerging future for Robert Burke?

Robert Burke: I'm very concerned about what sort of world we're going to leave our grandchildren's grandchildren. I am a grandfather now I'm concerned about that, but I'm also frustrated at the poor leadership that we're experienced. When you think about the pandemic, people like, Martin Rees , from Trinity college, a cosmologist wrote a book called Our Final Century. He only gave us a 50% chance of getting through it. And he said the major problem was going to be a pandemic. There was James Martin's book called the Blueprint for the Future where he had seventeen major challenges, 16 of which he said there were answers to, like global warming, but one that there was no answer to at the moment and that was the pandemic. And it always struck me why people ignored these scientists or these people who really cared about the future, who were telling us things that we should follow. So I became very frustrated if you like with leadership per se

Peter Hayward: Can I stop you there and ask you to tell me a story of how we got here? Because if we go back to Stacy, Argyris, Heifetz. Great people, bright people producing powerful documents about what leadership had to be effective. 40 years ago, 50 years ago, we had some of the most amazing people and ideas. And yet, if I was to look at it as a story arc, we are further, we seem to be to Peter Hayward, further away from the leadership that those people were articulating. We needed. And leadership on the face of it seems to be in retreat that we're looking at a leadership that even as I say, if you go back to Stacy's time, it'd be unrecognizable that these people are in leadership positions. Is it? It can't be that the leaders themselves are inferior. Is it something to do with the externalities and really, the volatility that we're getting the leadership we have now,

Robert Burke: Peter, I think it's lack of courage. And I think there are solutions . People who can do something about it tend not to. Particularly, if you look at the global warming, as you say, we've known about that for some time, people have told us what we should do, the fact that we haven't seems to me amazing. But it's a concern when you see those people that have leadership roles downplaying the significance of climate change, downplaying the significance of the threats to our very existence. I know only ignoring things like I will change, but ignoring what's going on in the world of geopolitics. I think a lot of it is due to our expectation that leaders have the answers and they believe themselves that they have answers. What would be far more courageous for them to say say, "I really don't know, but let's try to find out together." And I don't want to get personal about a lot of leaders, but I am horrified how poorly we as human beings are being played with, by people in powerful positions. I don't know if that sounds overly dramatic, but

Peter Hayward: I think it's, I asked for a story and to some extent you've given the story of, we, it's always been the saying that you get the leaders as you deserve. On the other hand, as Richard Slaughter always says, there are also are signs of hope. You've got to make the effort to look for that. Do you see the signs of hope?

Robert Burke: Yes, I do. I find a lot of the young people who are reacting to what they're seeing is going to infect their world, it's a sign of hope. I also think that science itself is a sign of hope. The idea that you could have vertical farming, for instance, Yeah, these 80 story farms that current produce four crops a year in the middle of the city, seems to me to be a wonderful idea.

The idea that a country, the size of Denmark could feed the entire world using vertical farming, according to professor DiSpirito from Columbia university. So I think those why of Science is good. I'd seen a university, one of the research centers there. I was introduced to a guy who had developed the Seneca beetle of the Nambia desert, which was both hydrophilic and hydrophobic.

It can produce its own water. And he came up with this process. If you like simplified it, like putting two pieces of polyurethane together, and you create water and I found this was brilliant that you can create your own water in places that water hadn't been seen before. That we could actually start helping people who are in real need name by simple science being put into practice, creating your own water, vertical farming, doing things differently, freeing up the animals. If you like. And all those things are possible. All they require is to give it a go do some prototyping, Singapore they have, saudi Arabia they have, and it seems to me it seems to be working well. I remember when I was at the business school in Melbourne, I did a calculation. I think we needed 80 of these towers to feed the entire population of Melbourne. I saw them as cooperatives where you'd have this, tower, this vertical farm, and underneath it you'd have the marketplace where people would all own it. We'd come and do their training. Get fresh food, slow food, seasonal, et cetera, and good nourishment, et cetera, in the middle of this city. And where we wouldn't have to have big farms where I had to have a lot of traffic. Also very interested in the piezo electric idea. That fact that stress can create energy. The idea that as you drive along the road, that you can create enough energy to have free energy in your motor vehicle, your truck or whatever. All seems possible to me, all same seems hopeful to me. That if we start to respect those scientists rather than to abuse them, which I think we do a lot, of we might get a lot of answers.

At the same time I was horrified to see the disrespect given to Humanities. The universities in favor of the STEM subjects. To me, education is about inquiry, not performance. It's about teaching people to think. And Humanities are certainly very important in that. So am I hopeful for the future? Yes. If we allow some of these ideas into fruition.

Yes. If we can add different programs to university courses like futures programs, like the one you ran at Swinburne. Yes. If we honor life itself and we start to respect that social classes don't exist, that we're all there and start helping people in a genuine way. I guess I'm influenced also by my daughter who is works for Oxfam in UK and she's quite inspirational about the work that lots and lots of people are doing that we don't actually recognize all the time. There is hope

Peter Hayward: And there should be concern too.. We should again, come back to your point. There are things to be anxious about. Yes. We should, but that anxiousness should galvanize us to act.

Robert Burke: It sounds ludicrous after we've seen the effects of wars, that way that I feel that we're on the brink of yet another one or that the anxiety of just day-to-day news articles being negative. That's like a treat not to have to listen to the news times. They need to be up to date, et cetera. But sometimes I feel that we rejoice in all these problems rather than think about how do we solve these problems? How do we get people to talk? How do we create a different narrative, a kinder narrative, a narrative that's going to enhance humanity, not destroy it.

Peter Hayward: The last question I'm going to ask you a question and. And we'll finish with this one, which is someone listening to Futurepod is starting out. Maybe not a CEO maybe it's just a small organization, maybe just starting out, trying to make a difference in their own way. But if you were to, with what you've learned and what you believe, without calling it advice and I'm not thinking you'll come up with the 10 things that are effective leaders do. Yeah. What is your sort of advice as to how a person goes about both building their own capacity, but also building the capacity of the people around them in order to do good work?

Robert Burke: My own feeling is to develop a sense of purpose. What enables us and what ennobles us. That to create something that is useful, something that you feel proud of, something that you're prepared to commit to. Do I advise young people going into a certain business. If they're really committed to it, only if they're prepared to understand that there'll be resistance, but that resistance can be actual learning. I was really struck by. Sohail's integral scenario method where you're integrated the Disowned with the Preferred. I found that extraordinarily powerful. And even if you were, you had a scenario that you didn't want, that you could completely avoid it, but you suddenly didn't think about if it did happen, how can I turn it into something useful? So I would encourage anyone starting out in business now to me, the most important area of study would be future thinking it enables them to have choices. It enables them to think differently, but to think more holistically and enables them to be kinder if you like.

And so to me, future thinking and leadership are one of the same thing, and that's the only reason you need a leader is to create some sort of preferred future. If that wasn't the case leadership wouldn't be required, management would do, but it is the case that we need to move forward. And it is the case that we need to develop people to be resilient enough to work at what I wanted to do, but also to have the courage of your convictions. And if you really believe in what you're doing and you did get knocked back, be able to get up and start again. On the other hand, if you get knocked down, maybe there is a reason for that.

Peter Hayward: I would think too Robert the other one too, which again, I don't think is different to what you're saying, but in your own story, you didn't try to do things by yourself. You found people to work with. Absolutely. And you found strength absolutely. Through collaboration.

Robert Burke: And I've always employed people who I thought were much better suited to the task than me so that, that had to have the technical skills, the rational skills, but they also need to develop a non-rational, the inner self. It was a great honor, actually, when I think about it, it's a wonderful role and I had to be a CEO. It has its trials and tribulations, but it also enables you, if you wish to take the challenge on to make a real difference. Like you're doing with these Futurepods. I think it's more conversations we have about what's possible and not possible, but really what's possible because we won't know what's possible unless we explore them. And I think futures thinking again, it's a way of exploring what's possible. So rather than put it in the background, it should be in the foreground. It should start in primary school.

Peter Hayward: Robert it's been great that we've been able to finally have this conversation and thanks for finding some time to have a chat to me and the futurepod community.

Robert Burke: Thank you very much, Peter. Really enjoyed it.

Peter Hayward: This has been another production from Futurepod. Futurepod is a not-for-profit venture. We exist through the generosity of our supporters. If you would like to support future pod, go to the Patreon link on our website. Thank you for listening. Remember to follow us on Instagram and Facebook. This is Peter Hayward saying goodbye for now.