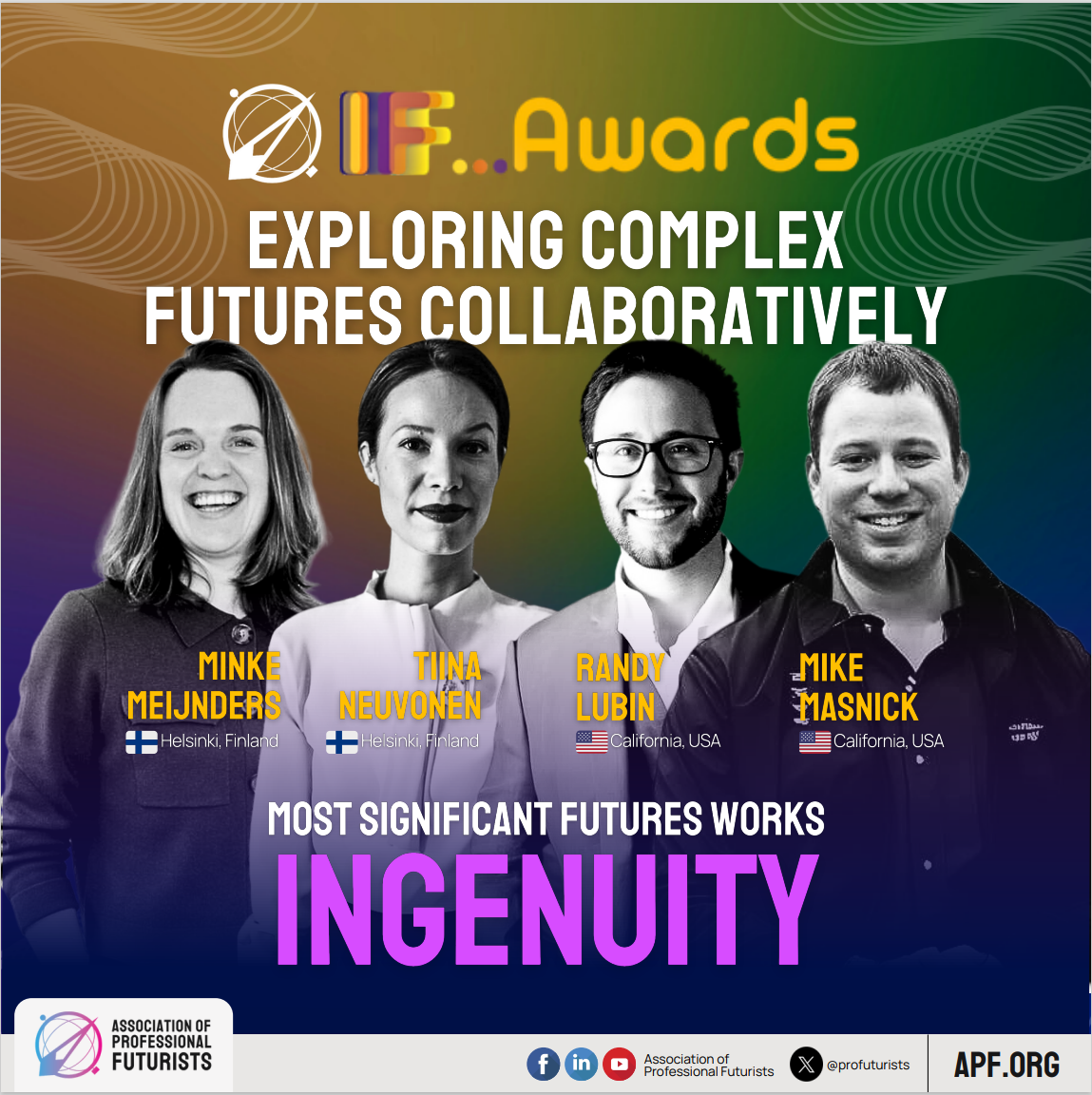

We are delighted to continue our new podcast series based on the Winners and honorable mentions from the APF 2023 IF Awards. Today we hear from Randy Lubin and Mike Masnick and their award-winning game, FutureCast, developed for the UN Global Pulse to help fragile democracies and Alex de las Heras whose documentary essay set in different locations in the Andean region explores future time, memory and decolonisation.

Interviewed by: Peter Hayward with Maggie Greyson and John Sweeney

Randy Lubin and Mike Masnick - FutureCast

Randy’s game design studio Leveraged Play

Mike’s Think Tank the Copia Institute

Alex de las Heras - ‘PAN’ Documentary Essay

Transcript

Peter Hayward: Welcome to the FuturePod Spotlight Series on the APF IF awards for 2023. In 2022 the APF changed from the most Significant Futures Work Awards to the IF Awards. Let's hear from Maggie what the IF awards are all about.

Maggie Greyson: The awards served as an invaluable resource for pointing clients. and the future's curiosity towards understanding the nature of work.

If questions, What If X, then y, are central to what we do as curators, facilitators, and researchers in supporting communities, organizations, and institutions to explore the futures.

John Sweeney: In celebration of the APF 20th anniversary, MSFW was re imagined as the APF IF Awards to reflect the globality, diversity, transdisciplinarity of the organization and the futures and foresight field. The Reimagined IF Awards program recognizes the evolving excellence in futures and foresight work with an emphasis on key thematic areas such as impact, imagination, and Indigenous.

Peter Hayward: Those awards are done and dusted and now we are here to celebrate the winners and special mentions. So get ready to hear from people doing important futures and foresight work all over the globe that is innovative, inclusive, indigenous, and much, much more. So on with the show.

John, who is my next person?

John Sweeney:Thanks, Peter. I'm thrilled that you're going to be speaking with Randy and Mike. They are winners in the Ingenuity category for their fantastic engagement exploring complex futures. This is an in person workshop game that was co designed with the United Nations Global Pulse team that allows players to explore opportunities and threats in complex settings that Through a collaborative and engaging process that, of course, leverages play.

What really sets this project apart is its unique design, which carefully navigates political sensitivities. It makes it particularly well suited for fragile political environments and even events like election day. And the game's lightweight and easily customizable nature really allows it to be adapted to various contexts.

You can play with experts, non experts, and ultimately, it's about broadening the foresight experience. And ultimately, how do we bring more voices into spaces, and of course, games are a great way to do that. Overall, Randy and Mike will talk about how the project represents a truly, a Interesting and dynamic approach to explore complex futures collaboratively.

It really does create that framework approach to be able to give people a way to think about the impacts that these events might have. And, of course, it's really dynamic that the UN system is actually using it. And to try to bring forward critical questions that, of course, can help those agencies and governments plan and work towards creating better futures for all.

Peter Hayward: Welcome back to FuturePod, Randy. And welcome to FuturePod, Mike.

Randy Lubin: Thanks for having us on the show. Happy to be here.

Peter Hayward: Congratulations on winning the category of Ingenuity for FutureCast, Most Significant Futures Work 2023. How does it feel to be considered by the Professional Association of Futurists to have produced something that's most significant work?

Randy Lubin: It's great. I feel like we've been, we've really come at foresight from our own angle and it's great to now be in more direct conversation with folks who've been practicing foresight for their, as their career for their career.

Mike Masnick: Yeah. A lot of it is that we view these things as different ways to explore different challenges and didn't think of it directly within the realm of the sort of foresight community.

And neither of us come directly from that field. So it was definitely an interesting and certainly validating experience to have them look at the work that we've done and this tool that we built in partnership with. The UN global pulse and find that, that people found value in it and found it a really interesting and exciting tool.

And yeah, it was very exciting for us.

Peter Hayward: Yeah, It's something you're going to hear me say a couple of times, this is for the listeners. If you have not been to the Futurecast website, go to it. It is absolutely brilliant as a piece of design for how to actually play the game. From an old game designer, that website is the best thing I've ever seen. And the game itself absolutely gobsmacked me. So who wants to go first, just to give a little bit of a quick little potted background about the work with Global Pulse and UN and why you did the game this particular way?

Randy Lubin: Sure, I can kick us off. To back up slightly further, Mike and I have been collaborating on games that explore the future and explain complex system dynamics for a number of years now, and a bunch of those have been about elections and democracy.

And so the UN Global Pulse reached out to us wanting to create a very easy to facilitate game to explore specifically questions around elections in fragile democracies. Maybe just a little bit more than a one party state where there's serious human rights concerns. And we knew that this was, there were a bunch of interesting constraints and parameters in the mix, but they wanted to bring our game design expertise to the table to figure out how can they create a tool, create a game that really empowers UN teams to explore risks and opportunities and pathways for positive change.

And so we immediately started brainstorming different possibilities working both with the Global Pulse team and with one specific country team that we were going to pilot it with and really trying to make sure that we were getting to a place where A given game session could generate meaningful insights for the country team, also be valuable for the participants, the players, while also protecting them too because we're focused on at least at first we were really focused on fragile democracies.

We wanted to make sure that we were not putting them at risk for any retribution from their home government. And so that was a lot of where we were at in the beginning. And then later we zoomed out and said, okay, how do we turn this into a broader framework and toolkit so that. Anyone in any country, any context can then customize this game to generate the types of insights that are most relevant to them.

Peter Hayward: Okay, that's a great quick summary. Now I'm going to unpack some of it because there's a lot going on in that Randy. I'm interested in both yours and Mike's philosophy so a game for you to be effective. And this is a very tricky process. You could design a game that was too complex. You could design a game that was too simple. You could design a game that was dangerous. You were navigating some really complex grounds yourselves, and you obviously have some principles that go into how you build good games to do futures inquiry.

Mike Masnick: Yeah, there's a lot there, and some of it was very much dependent on the partners that we were working with and making sure that we were meeting their needs, obviously. But a lot of what we're doing is taking kind of a combination of different principles and trying to apply them in a useful way.

Certainly understanding a little bit of the scenario planning world and how that works. And we knew that the UN global pulse team had experimented with scenario planning and had, we're building this ongoing scenario and, or a set of scenarios. And we wanted something that was practical and useful sort of on top of that or in conjunction with that, that this would be a very complimentary kind of thing.

And so what was really important to us was setting up a framework that really was able to help explore and bring out and extract where. People on the ground felt there were the real opportunities and threats that weren't necessarily obvious and weren't the types of things that you were likely to come up with through like traditional scenario planning.

And so from there, we just started to apply some of the concepts that we've used in other games in the past and trying to pull them together in a way that. Created a project that was again, relatively simple to for facilitators to take and make use of, and then also for the participants to play.

We didn't want something that was too complicated that required significant, significant amount of time to understand the rules. This is something that is relatively easily. To get into, there is some preparation time that is necessary, but then being able to take that and go further with it. Randy, did you have something?

Randy Lubin: I'll add from a process perspective, we like to be highly iterative and we think that's a really great way to make the game design process more accessible to different collaborators, both Global Pulse folks, as well as the country team. And, that also makes it more likely for us to discover flaws with the design early on, or conflicts or tensions or constraints.

We would, we'd quickly throw together a pitch, because we have, as Mike was saying, we have this big chest of different design mechanics that we've used in the past. And so we can quickly put together a proposal for, hey, here's what the game might be like, and then use that As a way of getting conversation from some of the different stakeholders and usually we'll pitch a few different versions.

They can compare and contrast trade offs of each. And then beyond that, we really love getting to testing as soon as possible. So sometimes that's what we'll call play storming where maybe it's just Mike and I, or maybe we'll put others to talk through just a part of the game and use that to sort of it.

quickly stress test, does this work like we think it might work? What are the edge cases? What are the pitfalls? And then keep iterating from there. And then ideally into play tests and different types of play tests as we get closer and closer to a final product.

Peter Hayward: When I look at the game and I look at what's on the website, you've got a game that people, if people just want to get in and play the game, there's a form that people can just jump in and play it almost to have the first experience. And then you can customize and build your own game.

Mike Masnick: We very much see it as a framework. And a tool that can be used in a variety of different contexts. And we provide some examples and starting points, but the setup of it can be very much customized for all different kinds of areas to explore.

If you're really trying to get people involved and engaged and explore where the different opportunities, challenges, threats, et cetera, might be coming from. We think this is a really useful framework for that purpose.

Peter Hayward: Now because you're talking about fragile democracy, then you're really not that interested in the futures. You are more interested in how people are behaving post the election. And so for me, you're using the future to really practice civic behavior. Is that a fair call?

Randy Lubin: I think it depends on context. In this case, we were using the upcoming election, which was several months after when the game was going to be run, as a lens to explore broader possibilities to expand civic space and ideally increase the health of democracy in this particular country.

And there were very immediate questions about civic behavior, but we also wanted to see how optimistic were people for the next election and the election after that and what were their hopes and what were pathways to moving in a direction of expanding civic participation, human rights, et cetera.

Mike Masnick: And in fact, the way the game is set up and again, like it, because of its nature as a framework, it can be used in different ways, but we definitely set it up in, in a manner that was designed to start in the near future. And then in future rounds go further and further into the future.

And there are a few different reasons for that. And part of it is just that it's easier for everybody to grasp the near future than automatically jump to a distant future. And so by doing this sort of gradual, step by step, pushing you a little further out and a little further out. It helps as, as far as we can tell, and in our experience to get people to.

To think, more reasonable, more reasonably in terms of thinking where things might be after a shorter timeframe and then a little further out and a little further out. And in fact, the exercise of going through the process of this game, for that round, you begin to think okay, here are things that might happen, maybe it's a few months out, maybe it's a year out, maybe it's two years out, and then you go to the next round and now you're thinking like, okay, You've already begun to think about these are changes that might happen in this timeframe.

Now I'm jumping forward even further, let's take that out a little bit further. And because of the nature of the game, I think like the issue and always the challenge with forecasting games is avoiding the pure extrapolation issue where it's like.

Here's the trend as it is today. Therefore, that trend line is just going to continue the really exciting things. And the really, the big aha's and the epiphanies come from like thinking beyond that and recognizing those trends, like obviously paying attention to those trends is important, but you're not getting the really important insights out of just extrapolating those trends but there's a lot in here that we hope gets people past that, keeps these trends in mind, but lets them see, like something that is unexpected, something that's coming around the corner, something that is bubbling up. From a part of the community or the society that hasn't gotten as much attention.

And part of that process is even this sort of step by step view of starting in the near future, but then we're going to step a little further and we're going to step a little further. And then some of the elements and some of the mechanics within here really are designed to force people.

Out of that thought process we're just going to extrapolate out and say if this is, from last year to today, this trend went this way, it's just going to continue in this straight line. We have some little tricks in there to try and force people out of that kind of thinking.

Randy Lubin: Yeah. It's one of the things that's very powerful, can be very powerful to do from a game design perspective and experience design perspective is to say, Hey, this major change has happened. So there's always an art to what you leave up to the players, or chance, versus code in. We can say that a transformative thing happens; in this case, maybe it's that an opposition party actually wins a huge number of seats in parliament.

And then we ask “how did this happen?” or “how will the majority party react to this?” We said: hey, a big discontinuity has occurred. Make sense of it.

Peter Hayward: Yeah. There have been quite a few games that have been acknowledged in the IF awards this year. I spent some time talking to Shermon Cruz and the Dreams and Disruption team. And they made the point that for them, disruption is the steel that sharpens their steel. In other words, disruptions makes you more anti fragile. It makes you better able rather than avoiding disruption, bring it on because if we can think our way through disruption, we're the stronger for it. I guess in your language, the democracy has to be able to deal with disruptions, and the more disruptive, the better test of what I would call their civic response to the disruption.

Randy Lubin: Definitely. And I think there's also a degree to which, you can look back on the famous quote of “never let a good crisis go to waste,” where if you've thought through and planned through and played through major disruptions, then when even if you're seeing in the real world, a major disruption happened that you didn't game out, the fact that you've thought through different pathways and have of how to act around it, you might be able to help steer the world, your context to a preferred future.

Peter Hayward: I'm interested in how it plays when you play it with younger people or decision making groups and political groups. Have you got some general case information about how the game plays with people?

Randy Lubin: So we were not on the ground in this country facilitating it. So we can only give you a little bit secondhand, but the first two play tests were with two very different groups of players. One was a group of civil service folks at NGOs, usually mid level to senior managers and leaders. And then the second group was with local youths who are, I believe, roughly college age.

And again, part of this was also testing how much we can tweak the game in a very easy way to tweak from a facilitator standpoint to ask the most relevant questions to the most, to the audience that you have in front of you. And so I know that there were definitely different sets of questions for each group really geared to get the right insights that could then feed into the outcome processes for the UN team that was running it.

And I also know it was really a high priority. For all the collaborators to make sure that the players felt like they were getting some good insights out of the game. That was a good use of their time, completely independent from what the game sponsor runners wanted to get out of it.

And so I know that after we ran the session with the civil society folks, during the debrief -which is always such a critical part of these types of experiences- we asked what takeaways they had from the game. And, if there would be any changes to plans they were making for their organization.

And without any specifics, we got very favorable feedback on both those points.

Mike Masnick: Yeah, I think, one of, it was almost the feedback that we got was, I think I would say almost surprising to, to the UN folks on the ground as to how positive it was and what, one of the things that we often think about because we're designing these games, but we're Designing them to be useful.

And the reason we're very upfront about calling them games is that we want them to be both educational, useful, and fun. And there's this element of when it's fun, It opens up different pathways for people to be thinking about it, right? If it's, if you're just going to a panel discussion or a workshop or a round table, you have a different impression of the whole thing.

If the exercise itself is just plain old fun, it lets people, I don't know if it lets down their guard a little bit, or…

Randy Lubin: Let down their guard is right. And maybe relax some of their ego and identity as an expert on a topic. And suddenly by either casting them into a different role or forcing them to ask very pointed questions, answer very pointed questions they suddenly have to give up on some of the Oh, I know the most likely thing that's going to happen.

And now they can generate some really interesting answers and insights and riff off of each other in ways that would not happen outside of a more gameful context.

Mike Masnick: Yeah. And I think there, there is something really to it that we've You know, we found in a lot of our games beyond just future cast, where it is, that combination of calling it a game, making people think they're playing a game and often like casting them in a role, like Randy said, is that it knocks down this barrier that, you know in, especially in professional contexts.

People want to come in and be the sort of expert in this area or present themselves. And they're often afraid to make a more outlandish suggestion or think outside the box. But when you're saying this is a game and you're taking on a role it frees them to do that.

And that allows them to explore different ideas that they might not otherwise have been willing to explore because they can say stuff that isn't. It doesn't get pinned back to them. It's okay. You're in this role. You're this character. What would you do in this scenario? How would you respond to this situation?

And we found that it is freeing in really interesting ways that provide a lot of really useful feedback.

Randy Lubin: Yeah. Yeah. It's an alibi, a really powerful alibi. And I'd say it also works in the reverse. It allows people to come in who are. have lower professional status or expertise and on a level playing field through their own ideas and intuitions out there because again they're now empowered to, to answer these questions and be in the spotlight.

Peter Hayward: Yeah, I was taught by a good friend of mine who when we worked together in organizations and often I played games and she was involved in the facilitating and she made a very strong point of saying to me that so much of what we do in work and organization, the work is not enjoyable. We're together to do work, but the actual things we're doing together are not enjoyable. And she said there is always merit in getting people who are trying to do difficult work, to give them an experience of working together and doing it both enjoyably and doing it well together. There's a huge thing for that in people because often our work times just are not enjoyable.

I would imagine that, FutureCast should roll out many times in many countries. That would be the point. You must now have ideas and things that you're interested in as a result of having done the FutureCast.

Randy Lubin: Yeah to your first point, yes, our hope is definitely that it gets played far and wide and we hope we've done a good job of designing the broader framework to, to make it customizable to local contexts and questions. And while it was originally designed for exploring elections and democracy, you can pivot it to climate change or innovation or any other topic without too much difficulty.

Yeah, we'd love to see it used. for all sorts of purposes. Likewise, we're really keen to see it used embedded in other planning and foresight processes. So maybe you're feeding in existing scenario plans or you're using it to embellish scenario plans and or any number of other planning processes.

Cause we think we like thinking in terms of how do these things connect together? What are the inputs and outputs? And hopefully this is a very flexible node that can be plugged into. to any process to, to enhance it. To your sort of second point we're always exploring new, how to use games in new contexts for new ideas.

We love remixing earlier mechanics that we've explored, so I'm sure we will pull on what we've learned with Futurecast. I think this was one of our first times that we spent a bunch of time beyond the initial design of the game in terms of thinking, how do we make it as easy as possible for others to customize it.

And that was a really interesting experience on our part and one that we will hopefully be able to continue doing. Mike, do you have other thoughts on that end?

Mike Masnick:Yeah, there's a bunch of different things. Again, the Futurecast setup is that it is a framework and there are a bunch of tools on the website about how people can customize it themselves.

We're also Available if people want to help with customizing it, feel free to reach out to us and we can see because we're interested in making this useful for others. We are always exploring other kinds of games. The two of us and others on our team have built a variety of different games around elections and about other future areas.

We've explored the future of artificial intelligence, which is obviously a very hot subject right now. We've explored the future of money in other contexts. We've looked at cybersecurity issues and others, and we're exploring, we've done a bunch of games on policy and internet services.

We've done a series of digital games. Most of these, most of the games that we've done we've done all different kinds of games, basically. This is an in person framework for hosting an in person event, but we've done digital games. We've done card games. We're exploring some other card games now as well.

And so we're really exploring a bunch of different topics. And right now we're looking at what is next and how else we can build useful, productive games for exploring complex topics and looking at the future and having a better understanding of it. We're, some of these games we're developing just on our own.

We're working with some partners as well with this, with FutureCast, we worked with the UN global pulse. We're always open to talking to different folks who are looking to create these tools or use these tools in an interesting way. One example of that is I think one of the games that we had created, that inspired the UN global pulse team to reach out to us, was a more specific election game called Threatcast 2020 that we created in 2019 that is a really useful tool specifically for exploring the impact of disinformation on elections. And so we have that in our pocket and we're. Now in a year where all around the world, there are a number of elections.

And so we're talking to folks about running it just as a tool to help prepare for how disinformation might impact other elections. And we're open to exploring all sorts of things, whether it's taking some of our existing games Whether election related or not, or creating entirely new games or adjusting some of our games we have all sorts of tools in our toolbox to use games in useful and productive ways.

Peter Hayward: Yeah. Certainly 2024 is the year of democracy. I think it's being called something like three or 4 billion people. That's got to be the single biggest year of democratic processes at a time of course when democracy would seem to be really not a slam dunk anymore now. It's under serious threat.

The thing I like to talk about is the notion of serious gaming. The game should be enjoyable. They should be participatory. They should be flexible. And they also can really be there as probably the best way to explore serious topics that if we sat around a table and tried to have a debate about it, we just finish up shouting at one another.

Randy Lubin: Yeah. We always see it as yeah, it helps build intuition. It helps build empathy for people very unlike yourself. And it creates a sense of what are the possibilities for the future.

Peter Hayward: Awesome. Fantastic work guys. Congratulations on your award. Thanks very much for participating and taking some time out to spend some time with the FuturePod community.

Randy Lubin: Thanks so much for having us on the show.

Mike Masnick: Yeah, this was great. Always fun to talk about this stuff.

Peter Hayward:I hope you are enjoying the podcast. Future pod is a not-for-profit venture. We are able to do podcasts like this one because of our patrons, like Sim who is one of our newest patrons. Thanks for the support Sim. If you'd like to join Sim as a patron of the Pod then please follow the Patreon link on our website. Now, back to the podcast.

Okay, John, who is our next person?

John Sweeney:I'm excited to share that Alex de la Haras received an honorable mention for his project entitled PAN, Exploring Time and Memory to Liberate Futures. This innovative series of five documentary essay chapters set in various locations in the Andean region, particularly Colombia, delves into conceptions of future time, memory, and the importance of decolonizing narratives.

By bringing together a diverse group of international collaborators, including knowledge keepers, artists, activists, and academics, Alex's project promotes inclusive and decolonial approaches to thinking about the future, specifically highlighting marginalized perspectives. What makes Pan truly unique is its innovative blending of documentary filmmaking with futures research, as well as its exploration of futures through the specific lens of Latin American and Andean contexts and colonialism.

The project challenges notions of presentism and utopian slash dystopian futures through a multi dimensional view of time, aiming to reconstruct historical narratives in a way that liberates from past burdens. Overall, Alex's project represents a compelling example of avant garde, boundary pushing work that embodies the values of inclusive, indigenous, and imaginative futures practices through its novel, creative approach.

Peter Hayward: Welcome to FuturePod, Alex.

Alex De Las Heras: Thank you, Peter. Good evening and good morning. Thank you so much for having me here I am delighted.

Peter Hayward: And congratulations on your honorable mention in the IF Awards of the APF.

Alex De Las Heras: Thank you very much.

Peter Hayward: I understand this work, PAN, came out of your PhD thesis and I think you called that Futures in the Present Continuos. So do you want to maybe explain to the listeners a little bit about that? That PhD, and then we'll move into PAN itself.

Alex De Las Heras: Sure. I titled 'Futures in the present continuous' referring to the multiplicity of possible scenarios and the current state of time and of mind in the Andean region.

Specifically in Colombia. I designed a methodology, which I named 'Spectiva' or 'Spective' in English, which combines participatory action research based on art with social foresight. Now this methodology, what it does is to put forward an experiential, performative and embodied shift in the futures.

As well at it showcases pedagogy of plural and multidimensional time. It stimulates notions such as the decolonization and the emancipation of the future. And by emancipation I it as a synonym of anticipation of the future, which is perhaps the most Western way of understanding how we can deal with the future on the present day, right?

Yep. And this Spectiva takes its name from the suffix that conveys the meaning of a case with the intentionality of triggering an action. So wWhile the retrospective gaze looks backward, the introspective one looks inward, and the perspective involves different points of views.

Foresight suggests a broad, a deep, and a forward looking gaze.

I specialize in experiential foresight narratives, but I also I'm a relational artist. So my background is in research creation practices,festive happenings, and in visual performance. And when I started this PhD, I came to the conclusion or to the thought that all too often it seems like we live in a present continuous, in the subsequent, in the moment that immediately follows, in a presentism, and in a fixation of the short term, which is in the case of the Colombian and the Andean region represented by a constellation of different historical horizons.

Quoting Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, she points out that these horizons, not having been resolved in the past, they have started to accumulate in the present, adding to new conflicts and to the tense that produces the future itself. So how can we overcome this situation? How can we overcome this being tangled in between pasts that do not pass and presents that seem never to arrive.

Peter Hayward: That struck me that in PAN, when you were traveling in that gondola with that woman over the houses and you asked her, is this the future? And she told a story that was mythic in how this was both past and the mountain itself was going to punish us for this. It struck me as you talked about this notion of entangled narratives.

Alex De Las Heras: I think every discussion about the future has a discussion about time.

When we think about Columbia it is not that easy to think of future from a Western point of view, which obviously occurs, but there are other points of views too. There are other representations of time. There are not only linear, there's multi temporality, there's cycle, there are different conceptions on how we understand time.

And in PAN, this is reflected. So there are different participants who bring their different representations of time, to some of which, the future does not exist, solely past and present. .

So there's always this question of what time is. Some of the people who participated in PAN also pointed out that perhaps there's no future or that to think of future, it's something that it's ungraspable for them,

There's also a social class, a racial , and a gender aspect on future time, at the time of prepping the future. There's something more about PAN , it's a project that it spanned from 2019 to 2023. And in 2019 we had seismic movement, a social movement in Colombia,. This was a huge social awake. And this is also something which is represented in the documentary. There's a shift. On the way they think there's a shift on the way they imagine the futures in 2019 and there's a shift on how they imagine these same futures in 2020 with the context of the Covid pandemic and in 2021.

Peter Hayward: I'm interested through the your research and the documentary, whether you noticed, differences in cohorts? When you spoke to people who were, again, my age, elderly, when you spoke to people middle age, and then when you spoke to young people, are the perspectives also mixed up in those generational cohorts?

Alex De Las Heras: Yeah, sure. In the end in PAN there's a huge group of participants. Most of them, they belong to the cultural scene. They're also cultural heritage keepers, bearers, there are artists and activists and the ages swift between the twenties and the sixties, seventies years old. Of course, in 2019, it was mainly young movement, a student movement.

the one who, who really pushed forward the different strikes against the government and against a present continuous situation they have in Columbia. But there was also great support from the elders . Now, when you ask about the future, of course , the younger people can imagine 10 years ahead, 20 years ahead, and they can imagine a different society perhaps.

They imagine if they ever imagined before the future, they imagined themselves and their families and their closest people and how they would like to live their society. But for the elders, it changes because they have a stronger memory. They have developed they have lived and experienced a greater deal of life.

And this changes the perception in which and how they see the future. This changes. It's, I think it's obvious. If we ask children how they can imagine the future, there are no limits, but age has a limit and memory and all those conflicts which have been anchored in the collective memory, they have a big limit on how we imagine the future.

So for the elders, it's more about how we break those horizons and how we overcome something that we have been pushing for years or for decades, while for the youngsters, it's more about breaking the present moment and which allows us to perhaps create sustainable futures.

Peter Hayward: So the notion of the deep, the decolonizing of the future is the notion of changing memory of what the past was in order to open the future?

Alex De Las Heras: I think that's one possible point of view, sure, but in PAN there's a question about colonial images of the future. Part of PAN, one of the chapters, two of them actually happen inside of a Baroque church from the 17th - 18th century. And this Baroque church has now something which is understood as Religious art, which at the time back in the 17th and 18th century could have been understood as images of the future, images of the future family, images of the future behavior, right?

So there's something important there. And it's that the images of the future have been created and have been formulated and communicated all along history. So some of these future images have built the colonial subject of today. And if we want to decolonize the future, then I think it is also important to go back to the past and reinterpret this images, re understand this images.

Is

Peter Hayward: You had a video of the people playing bongos and a performance in that church?

Alex De Las Heras: Yes. Actually, my very first research project mixed celebration, festive happenings with future. To me, celebration and festivity, it's a great immersive scenario where we can talk about the future and we can imagine ourselves staging possible futures.

This happening you're talking about was called' The First Council of Festive Devils to celebrate the Futures of Humanity', and it was directed together in collaboration with the historian and researcher Paolo Vignolo from the National University of Columbia. And it was hosted during the Official Academic Program of the 14th Meeting of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safe Guarding of the intangible cultural heritage of UNESCO.

Wow. What a title. Yes, it's a long name. I took some years to learn it, to pronounce it. This happening event was a little bit of a hack and a game. We didn't tell them everything that was going to actually happen there. We just told them that we were calling about 120 festive devils to perform an intangible culture happening.

And festive devils

are a folk character in the Caribbean and Latin America. And it's a very interesting folk character because it also talks about the future itself. Now, if we think about festive devil, it is composed by two words, festivity and devil. The devil was a subject, or an icon more than a subject, which was brought to the colonies to control, while festivity 'fiestas' as we know them in Columbia were also brought as a result of the transatlantic exchange for centuries.

This character itself, it talks about this process of colonization, but it also talks about the process of decolonization because it breaks the rules. So we thought in our playful minds, we thought how fun it would be to bring 120 devils coming from Colombia, from Austria, from Spain, from Italy, from Chile, from different regions, put them all together into this Baroque church, which is today a deconsecrated church.

It is a museum, which has more than 300 years of devotions and future images and give them their a script, a canovaccio to work on the resignification of this space, to celebrate their existence in this space. This turned to be a marvelous night, a fun night.

Everyone, we had a lot of fun. Some of the images and the gestures and the actions which happened were just absolutely magnificent. There was one collective, which is called La Mujer Cabra, so the goat woman, who stood up in the pulpit and she was singing a song about the future of the indigenous guard in Colombia.

And this was very powerful. So there were many different performances going on at the same time, but we had also prepared a last action and performance, which was to come out of this museum, which is in the presidential corridor , where the president lives in Columbia at the moment and have a great collective laugh.

So laughing and laughing out loud as a gesture of future of a collective. So it all starts there. And it's actually I had very clear that I had to document every process that was happening during this this event. And it is about from all this document and all this recording that I made at this time with an amazing group of a team of collaborators that PAN emerges,

PAN starts as a methodology there. So getting this material and curating this material after playing after wondering about time and staging different futures scenarios, you get all of this. And what do you do? How do you classify this stuff? And most importantly, how do you bring it back to the people who participated in that happening?

How do you exchange ideas about what happened there and how it made them feel and what notions of future they have started to develop over time. So that's why it took so long to produce it from 2019 to 2023, because there was this constant communication with this group of participants on how this future was being built and what it meant.

Peter Hayward: So getting towards the end of our very short chat, Alex, if listeners want to see PAN or find out more about you and the methods, are there ways that they can do that?

Alex De Las Heras: You can always go to my website. This is www.alexdelasheras.es I also have one chapter of PAN which is hosted at the Hemispheric Encounters Network.

Yep. This is https://hemisphericencounters.ca/projects/pan/ . You can also read soon enough an article about 'Spectiva' the method that I used and I designed for this PhD research. It will be published on good publication about futurisms in Latin America. And you can also find my PhD Thesis 'Futures in the Present Continuos' in the National University of Colombia's repository.

Peter Hayward: All that information will be available on your show page. As I suppose, lastly, Alex, what do you hope, what is the future for PAN?

Alex De Las Heras:

I think the most important thing for PAN is to travel back to the territories and the communities where it has been documented and recorded. This would be bring it back to the north of Chile, in Pisagua, where the festive devils of La Tirana participated. It would be also very important to bring it to Caquetá, in Colombia, where the Inga community lives and has also participated.

I would love also to project it in Bogota again. So I think it has to go back to return to its roots. And I think that's also something I value very much about working future projects. Once that they are somehow finished, they should return with all the changes that they have created to the places of origin and then see if they actually worked, if they were worth something, if they actually triggered something.

I think that's the imminent or the future I would like the most at the moment for PAN. And of course I dream every day about other futures, but I think that's the main. I can also say is that I have been awarded a postdoctoral fellowship at York university in the Connected Minds laboratory.

And I will be applying the 'Spectiva' methodology on a new project, which also which deals with visions of tomorrow: exploring fiestas, data visualization, and virtual reality in shaping Colombia's post conflict future. So that will be also a window to know more about my work.

Peter Hayward: Fantastic, Alex. On behalf of the FuturePod community, thank you very much for taking some time out to explain and tell us the story of yourself and PAN. Also, congratulations again on your Honourable Mention in the APF IF Awards.

Alex De Las Heras: Thank you very much, Peter.

Peter Hayward: I hope you enjoyed meeting today's guests. Mike and Randy and their very, very needed game to promote and strengthen democracy through play and conversation. And Alex and his cultural and critical exploration of Andean culture and time. I will catch you next time and I'll let John close us out.

John Sweeney:Hi, everyone. Keep an eye out for the Association of Professional Futurists call for submissions for the IF Awards come August. If you have a futures project you're working on or considering, this is a fantastic opportunity to share it with the APF and the broader futures and foresight community. The IF Awards recognize excellence in futures and foresight work across nine themes, such as Impact, Imagination, and Indigenous. Stay tuned for insights from past winners published in Compass, And the upcoming APF membership events.